Problem:

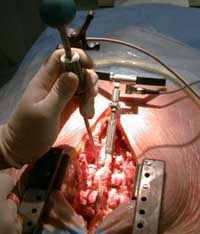

A 43 year old male returns from the operating room following cholecystectomy. The operation had been originally planned using the laparoscopic approach. However it became necessary to convert to an open procedure. Intraoperatively the patient received fentanyl 300mic/g, propofol, vecuronium, oxygen and desflurane and cefazolin. At the end of surgery, neuromuscular blockade (sustained tetanus was demonstrated) was reversed, the patient opened his eyes and was extubated.

On arrival to the recovery room the patient is combative, thrashing around, incoherent, not obeying commands, attempting to remove has urinary catheter. His pulse rate is 120 beats per minute, blood pressure 170/100, temperature 37.0 degrees Celcius and his pulse oximeter is reading an SpO2 of 99%.

1. Identify the problem

What is the mechanism of injury and what are the treatment options?

This patient is agitated: the most common cause of postoperative agitation is pain. Pain is a neurohormonal and emotional response to a noxious stimulus, in this case surgical injury. Pain is the “fifth vital sign.”

Pain is known to worsen perioperative outcomes: it results in – increased protein catabolism – thereby reducing physiologic reserve, retention of salt and water, impaired wound healing, prolonged recumbent times (resulting in increased risk of deep venous thrombosis), and significant suffering and dissatisfaction on the part of the patient. Elevated adrenergic activity results in increased oxygen demand and may precipitate myocardial ischemia. In patients, such as in this case, that undergo upper abdominal surgery, the splinting effect of pain results in impaired coughing and lung derecruitment and increased risk of pulmonary complications including nosocomial pneumonia.

One of the major roles of perioperative clinicians is to minimize patient suffering. Patients universally report dissatisfaction with perioperative pain management.1 Modern approaches to preventing suffering in perioperative patients include a multimodal approach to pain, postoperative nausea and vomiting, anxiety, agitation and delirium.2-5

2. Understand the problem

What is pain (understanding the mechanisms)?

Table 1. Inflammatory Mediators that amplify the pain response

|

Substance

|

Source

|

| Norepinephrine |

Nerve endings & circulating |

| Epinephrine |

Circulating |

| Substance P |

Nerve endings |

| Glutamate |

Nerve endings |

| Bradykinin |

Plasma kininogen |

| Histamine |

Platelets, mast cells |

| Hydrogen Ions (acidity) |

Ischemia / Cell Damage |

| Protaglandins |

Arachidonic acid / damaged cells |

| Interleukins |

Mast Cells |

| Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

Mast Cells |

Surgical incision is associated with tissue injury and release of inflammatory mediators, development of local edema and activation of nocioceptors. These are nerve endings of myelinated (A-delta) and unmyelinated (C) afferent nerve fibres that respond to noxious thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimulation. A-delta fibres are mechanothermal while the C fibres are polymodal.

When nociceptors are activated, a series of neurohormonal reflexes are activated, and a painful sensation is elicited.6 In the awake patient, this is apparent by an adverse emotional response, a sensation of “unpleasantness”. In a sedated patient this may result in hyperadrenergic activity, agitation or aggressiveness.

Figure 1: Pain Pathways

1. The nocioceptive response is activated at the level of the surgical incision; 2. release of inflammatory cytokines and vasodilator metabolites; 3 transmission of nocioceptor impulses along afferent A-delta and C fibers; 4. integration and amplification in the spinal cord – c”windup”; 5 transfer of impulses from doral horns to thalamus and post-central gyrus; 6. activation of hypothalmo-pituitary adrenal axis; 7 release of cortisol, epinephrine and norepinephrine; 8 central and peripheral sensitization .

Normally, there is a relatively high threshold for activating nocioceptors. However, tissue injury alters the activity of these neurones, due to the local production of inflammatory mediators (an “inflammatory soup” table 1). These include substance P, glutamate, bradykinin, histamine and arachadonic acid metabolites, such as prostaglandins. Their impact is twofold, to directly activate nocioceptors, and to reduce the firing threshold of these receptors.7 This is traditionally known as peripheral sensitization: lower stimuli than usual result in pain sensation. This is amplified in part by the systemic production of catecholamines secondary to activation of the hypothalmo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Moreover, epinephrine and norepinephrine induce a state of anxiety and diaphoresis that worsens the emotional response (figure 1). In addition, tissue trauma activates inflammation, and inflammation causes pain. Inflammation causes pain through the up-regulation of stimulated nociceptors and the recruitment of nonstimulated or dormant receptors.8 Proinflammatory mediatiors such as interferons, tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1 and interleukin 6 decrease the threshold for impulse generation and increase the intensity of the nocioceptive response.7 A patient emerging from anesthesia with elevated levels of stress hormones (cortisol and catecholamines) that is experiencing significant pain, will frequently become agitated and inappropriate, as in this clinical scenario.

Nocioceptor activation results in all-or-nothing depolarization of the afferent nerve. Painful impulses are transmitted to the dorsal horn spinal cord and subsequently to the thalamus and the post central gyrus. In the spinal cord central sensitization may occur.9 A sufficiently strong stimulus may change the interpretation of painful impulses and subsequent stimuli are amplified. An area of hyperalgesia, composed of undamaged tissue, may appear adjacent to the injured site.10 This is due to “windup”, which results from repetitive C-fiber stimulation, mediated by glutamate via n methyl d aspartate (NMDA) receptors.11

Second order neurones synapse at the level of the spinal cord and transmit pain signals to the brain. Two predominant types of second order neurones have been identified: wide dynamic range (WDR) neurones and nociceptive specific (NS) neurones. Nociceptive signals ascend in the spinothalamic and spinoreticular tracts. These fibres project to multiple sites in the brain stem and midbrain, including the brain stem autonomic regulatory sites, hypothalmus and thalmus.

The body does have a pain regulating system that attenuates the response. This is modulated by a variety of neurotransmitters and inhibitory interneurones, that utilize endogenous encephalins and endophins and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA). The binding of these endogenous opioids to central and peripheral receptors results in reduced presynaptic release of neurotransmitters, in particular substance P, and curtailed nocioceptor response.7

MANAGING PAIN – TREATMENT OPTIONS

Opioids

Opioids remain the mainstay of treatment for postoperative analgesia. Opioids exert their effects by binding to an array of receptors (“opioid receptors” μ, κ and δ) that exist in the central and peripheral nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. This results in analgesia and an array of characteristic side effects (table 2). In addition, opioids may have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects.7 A variety of naturally occurring, synthetic and semi-synthetic opioid agents are available for therapeutic use. These include full μ receptor agonists, partial agonists and agonists/antagonists (table 3). The choice of agent is dependent on the practice patterns of the clinician The majority of us use limited selection of full opioid receptor agonists, including morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone, meperidine and methadone. Tramadol and codeine are weak receptor agonists.

| Table 2: Side effects of Opioids |

| Pruritus |

| Nausea and Vomiting |

| Sedation |

| Dysphoria |

| Respiratory Depression |

| Urinary retention |

| Constipation |

| Hypotension |

| Bradycardia |

| Urticaria |

| Confusion |

Physicochemical Properties of opioids

There are two physiochemical properties of opioids that determine their pharmacologic action (table 4): degree of ionization and lipid solubility. Opioids are weak bases. When dissolved in solution, they are dissociated into protonated and free-base fractions, with the relative proportions depending on the pH and pKa. The more unionized the agent, the more rapid its onset of action (table 3): hence alfentanil, which is 80% unionized (it has a pKa of 6.1) and remifentanil which is 70% unionized (pKa 7.1,) have more rapid onset of action than fentanyl (<10% unionized, pKa 8.4).

Lipid solubility is determined by the chemical structure of the agent. The more lipid soluble the agent the more easily the agent passes thru the blood brain barrier to the site of action. This also impacts onset of action: hence fentanyl has a more rapid onset of action than sufentanil which is more rapid thanmorphine or hydromorphone. Lipid solubility also impacts the volume of distribution of the agent: the higher the lipid co-efficient, the greater the amount of the drug sequestered in fat stores in the body. This is important when opioids are used as continuous infusions, resulting in a complex pharmacologic process known as “context sensitive half time.”

After intravenous injection, arterial plasma concentrations of opioids rise to a peak within one circulation time. Thereafter, they exhibit a rapid redistribution phase and a slower elimination phase typical of drugs whose pharmacokinetics are described by multi-compartmental models. Drugs that are more lipid soluble, such as fentanyl and sufentanil, redistribute extensively to fat, including non receptor fatty tissue in the brain. Alfentanil and remifentanil, agents that are not lipid soluble, have low volume of distribution and are rapidly cleared from plasma. Morphine, hydromorphone and meperidine have relatively low lipid solubility and are extensively metabolized by the liver. They have relatively long duration of action. Fentanyl and similar agents are also extensively cleared by the lungs.

|

Table 3: Opioid Agents available of Postoperative Analgesia

|

|

Agent

|

Dose im/iv

|

Oral Dose

|

Morphine 10mg equal to:

|

Onset (min) iv

|

Peak Effect (min)

|

Duration

|

|

Alfentanil

|

500mg

|

NA

|

300mg

|

<1

|

1-2

|

10-20 min

|

|

Buprennorphine

|

0.3mg

|

0.5mg

|

2.5mg

|

15

|

60

|

5 hr

|

|

Butorphanol

|

1-4 mg

|

1 mg

|

2 mg

|

5-10

|

45

|

3-4 hr

|

|

Codeine

|

103 mg

|

200 mg

|

130 mg

|

30

|

60

|

3-4 hr

|

|

Dezocine

|

5-10mg

|

NA

|

10 mg

|

15-30

|

60-90

|

3-4 hr

|

|

Fentanyl

|

100 mg

|

NA

|

125 mg

|

0.5

|

5

|

1 hr

|

|

Hydromorphone

|

2 mg

|

4mg

|

1.3 mg

|

15-30

|

2-3

|

30-60 min

|

|

Levorphanol

|

2 mg

|

2-3 mg

|

2.3 mg

|

25

|

45

|

6-8 hr

|

|

Meperidine

|

50-100 mg

|

100mg

|

75 mg

|

1- 2

|

30-60

|

2-4 hr

|

|

Methadone

|

2.5-10 mg

|

2.5-10 mg

|

10 mg

|

30-60

|

30-60

|

4-6 hr

|

|

Morphine

|

10 mg

|

30-60 mg

|

10 mg

|

2-3

|

20

|

4 hr

|

|

Nalbuphine

|

10 mg

|

NA

|

12 mg

|

2-3

|

30

|

4-6 hr

|

|

Oxycodone

|

NA

|

5 mg

|

10 mg

|

15-30 (PO)

|

60

|

4 hr

|

|

Oxymorphine

|

1 mg

|

NA

|

1.1

|

1-2

|

30-60

|

4-6 hr

|

|

Pentazocine

|

30 mg

|

50 mg

|

60 mg

|

15-30

|

100

|

3-4 hr

|

|

Propoxyphene

|

NA

|

200 mg

|

200 mg

|

15-30 (PO)

|

120

|

4 hr

|

|

Sufentanil

|

20 mg

|

NA

|

12.5 mg

|

<1

|

2

|

30-45 min

|

Morphine

Morphine, a component of opium, has been used for analgesia and anxiolysis for millennia. If was first purified by Serturner, a German pharmacist, in 1803. He called this alkaloid “Morphia” after Morpheus, the Greek God of Dreams. Morphine is a phenanthrene opioid receptor agonist that exerts its major effects on the CNS and gastrointestinal tract. It is the prototype opioid analgesic agent, against which all other agents are compared. The majority of healthcare professionals are familiar with this drug in terms of its clinical effects, dosing and complications. This imparts a significant degree of safety; as a result I recommend morphine as the first line analgesic agent in PACU.

Following injection the onset of analgesic effect of morphine is 5 minutes with a peak effect at 20 minutes. Morphine is predominantly unionized (pKa 8.0) and has low lipid solubility: penetration into the brain is consequently relatively slow (table 4). Patients experience mild sedation prior to analgesia. This makes morphine an ideal analgesic agent for patients that are agitated and in pain, such as in this scenario, and patients requiring mild sedation for mechanical ventilation in the PACU or ICU. Conversely, the neurologic assessment of patients with brain injuries of following neurosurgery may be clouded by this effect.

Single boluses of morphine may be ineffective to establish adequate analgesia. Aggressive “loading” with the drug, to break the cycle of pain, may be required. This requires careful titration to analgesic and sedative response (figure 2).

| Table 4 : Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic data of commonly used opioid agonists |

| |

Morphine |

Meperidine |

Fentanyl |

Sufentanil |

Alfentanil |

Remifentanil |

| pKa |

8.0 |

8.5 |

8.4 |

8.0 |

6.5 |

7.1 |

| % Un-ionized at pH 7.4 |

23 |

<10 |

<10 |

20 |

90 |

67 |

| Partition Co-efficient |

1 |

32 |

955 |

1727 |

129 |

16 |

| % Bound to plasma protein |

20–40 |

39 |

84 |

93 |

92 |

80? |

| Elimination half time (hours) |

1.7-3.3 |

3.0-5.0 |

3.0-6.6 |

2.2-4.6 |

1.4-1.5 |

0.17-0.33 |

Morphine is known to have a direct histamine releasing effect. While the clinical implications of this are generally overstated, transient vasodilatation and hypotension may result. This is an unlikely problem in hyperadrenergic postoperative patients complaining of pain, but may be an issue in patients under general anesthesia or who are receiving concomitant propofol infusions. Morphine may cause euphoria. It alters the perception of pain: the patient knows that he/she is in pain, but is not bothered by it.

Figure 2: Effect of administration recurrent boluses of morphine on pain, and sedation in a typical postoperative patient in PACU. VAS = visual analog score; RASS = Richmond agitation sedation scale.

Morphine has an important side effect profile (table 2): it is a direct respiratory depressant, and acts by reducing the respiratory center’s responsiveness to carbon dioxide. Morphine induces nausea and vomiting by an effect on the chemoreceptor trigger zone. It induces miosis (pupillary constriction), causes constipation, may cause urinary retention and causes cutaneous vasodilatation. Morphine is a potent anti-tussive agent; again this may be beneficial in mechanically ventilated patients. Morphine is principally metabolized by conjugation in the liver, to morphine 3-glucuronide (M3G), which is inactive and morphine 6-glucuronide (M6G), which is highly potent. There is also some extrahepatic metabolism in the kidney. Hence care should be taken when morphine is administered to patients with significant renal impairment, as delayed respiratory depression may follow.

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone is structurally very similar to morphine. It differs from morphine by the presence of a 6-keto group and the hydrogenation of the double bond at the 7-8 position of the molecule.12 It principally acts at µ receptors, and thus shares a similar side effect profile. Hydromorphone is slightly more lipid soluble than morphine, and has a slightly quicker onset of action; its peak effect is at 20 minutes. Hydromorphone is less sedating than morphine and does not have active metabolites (although it is metabolized by the liver and metabolites accumulate in renal failure). Hydromorphone is widely used for patient controlled analgesia and for intravenous analgesia in the ICU. The major limitation of using hydromorphone is confusion regarding the appropriate bolus dose. Hydromorphone is roughly 7.5 times more potent than morphine; as a result one is more likely to encounter accidental (due to prescription error) overdose with this agent.

Fentanyl

Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil and remifentanil are semi synthetic opioids that have rapid onset and relatively short duration of action. Only fentanyl is routinely used for postoperative analgesia. It may be administered intravenously as bolus or infusion, transdermally through a patch or novel transcutaneous delivery systems, transorally (fentanyl “lollipop”), intrathecally or epidurally.13

Fentanyl has relatively rapid onset of action (1-2 minutes peak effect 5 mins) and short duration of action (20 minutes). However its therapeutic window is relatively narrow. When fentanyl is administered in low to moderate dose (1-5 mic/kg) intraoperatively, there may be little or no residual drug effect by the time the patient arrives in PACU. The patient may experience severe pain.

Fentanyl is highly lipophilic and redistributes to fat stores in the body; this may result in significant accumulation if given in high dosage. Its context sensitive half time is relatively long if administered by infusion. The complex pharmacology of fentanyl limits its effectiveness for perioperative analgesia. For prolonged effect, high dosage (5-15mic/kg) need to be administered, risking significant respiratory depression. Tachyphylaxis develops rapidly resulting in reduced effectiveness with escalating dose. This may result in significant problems such as ileus and urinary retention.

Although fentanyl can be used for analgesia in PACU, its effectiveness is limited to short episodes of analgesia, for example if coverage is required during a procedure – such as placement of a chest tube or epidural. It is not an effective agent for significant visceral pain unless given as an infusion or thru a PCA (patient controlled analgesia device). Transcutaneous fentanyl patches have slow onset of action and have no role in acute pain management. Newer products that utilize iontophoresis (a non-invasive method of propelling high concentrations of a charged substance transdermally using a small electrical charge), may make patient controlled fentanyl administration popular for ambulatory surgery.

Meperidine (Pethedine)

Meperidine is a semi-synthetic opioid structurally similar to fentanyl. Meperidine is one-tenth as potent as morphine. Meperidine is an effective analgesic and, in equianalgesic dosage, produces as much sedation, euphoria, respiratory depression and nausea and vomiting as morphine. Meperidine is significantly different pharmacologically to morphine, and has effects on a medley of receptors (see chapter on shivering). Of interest, meperidine has atropine like effects. The majority of opioids cause bradycardia, presumably by a direct or indirect action on the hypothalmo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Meperidine induces tachycardia. It also causes papillary dilatation. Meperidine has no anti-tussive effects. It has smooth muscle relaxing effects, and was used traditionally as analgesic for heptobiliary and ureteric surgery. However there is no evidence that this agent is superior to morphine in these situations. Meperidine causes less constipation and urinary retention than morphine. It has been used for generations for intramuscular analgesia in labor. The major current clinical use of meperidine is for treatment of postoperative anesthesia related shivering.

The major limitation of meperidine is its active metabolites: normeperidine (norpethidine) and meperidinic acid. Normeperidine accumulates, particularly in renal failure and may cause CNS stimulation (seizures or myoclonus)

Tramadol

Tramadol is an atypical opioid which is a centrally acting analgesic, used for treating mild to moderate pain. It is a synthetic agent, as a 4-phenyl-piperidine analogue of codeine.It can be administered orally or intravenously.

Tramadol is approximately 10% as potent as morphine, when given intravenously. It has effects on opioid, GABAergic, noradrenergic, NMDA (antagonism) and serotonergic receptors. Analgesia with tramadol is not fully reversed with naloxone although it has weak affinity for the μ-opioid receptor (approximately 1/6th that of morphine). The major issue with this agent is the serotonin modulating properties that may lead to interaction with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and result in serotonin syndrome (see chapter on malignant hyperpyrexia).

Tramadol causes significantly less respiratory depression and bowel dysfunction than conventional opioid analgesics.14 It does cause nausea and vomiting and may reduce seizure threshold.

Patient Controlled Analgesia

There is tremendous inter-patient variability in postoperative analgesic requirements. Coupled with greater demands on, and reduced availability of, nurses on postoperative wards, patient controlled analgesia has emerged as the gold standard delivery system for postoperative pain relief.15 Patients prefer PCA to nurse administered analgesia.16 Dolin and colleagues17 collected pooled postoperative pain scores from 165 publications and concluded that the mean incidence of moderate to severe pain was 67.2% and that of severe pain 29.1% for intramuscular opioids. The corresponding values were 35.8% and 10.4% for PCA, and 20.9% and 7.8% for epidural analgesia, respectively. The superiority of epidural analgesia has been confirmed by other investigators.18 Nonetheless, PCA, compared with conventional opioid treatment, improves analgesia and decreases the risk of pulmonary complications.19 In a large meta-analysis of fifty-five studies with 2023 patients receiving PCA and 1838 patients assigned to a control (parenteral ‘as-needed’ analgesia), PCA provided better pain control and greater patient satisfaction.20 Patients using PCA consumed higher amounts of opioids than the controls and had a higher incidence of pruritus (itching) but had a similar incidence of other adverse effects. There was no difference in the length of hospital stay.

Surprisingly, these results were not seen in many studies. This probably relates to the tremendous variability in settings applied to PCA devices: bolus doses, lockout, background infusions, opioid agents used etc.21 PCA strategy should be titrated to patient requirements. The best available evidence suggests that the optimal bolus dose of morphine is 1mg.22 Initial IV-PCA bolus doses of other drugs that are commonly used for opioid-naive patients are hydromorphone, 0.2 mg; fentanyl, 20 to 40 μg.21 The lockout interval is used to limit the frequency of demands made by the patient within a certain time. Lockout periods between 5 and 10 minutes are commonly prescribed. If analgesia is inadequate with a certain lockout period, it is more effective to increase the bolus dose rather than reducing the lockout.23 The use of a background infusion with IV-PCA, in addition to bolus doses on demand, is targeted at improving patient comfort and sleep: the expectation is that the patient will not awaken in pain. However, studies report no benefit to pain relief or sleep and no decrease in the number of demands made but a marked increase in the risk of respiratory depression.21 Background infusions should be limited to use in chronic opioid users.

Multimodal Analgesia

The concept of multimodal analgesia is based on the observation that pain is a multifactorial phenomenon – amplified and modulated at different sites both peripherally and centrally, and is therefore not amenable to control by opioid monotherapy alone.2;4;5

Figure 3: Multimodal Analgesia: a balanced approach to analgesia – different agents are combined to reduce pain transmission at different sites, targeting local nerves and neurotransmitters, the CNS and the neuroendocrine system.

The multimodal approach to perioperative pain management involves attenuating nociceptive activity at many different levels (Figure 3), including:

- Reducing nocioception output at the surgical site, by superficial and deep wound infiltration.

- Treating and preventing peripheral inflammation using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Blocking afferent nerve activity by regional blockade using local anesthetics with or without other agents (opioids, tramadol, and ketamine). This blockade may be involve peripheral nerves (inguinal field block) neural plexuses (brachial or lumbar plexus block) or spinal level (subarachnoid or epidural block)

- Modulating central pain processes at the level of the brain or spinal cord (e.g., opioids, tramadol, NMDA antagonists, alpha-agonists). Some agents, such as opioids, have been shown to work at a number of levels (peripheral, spinal, cerebral).

- Reducing adrenergic activity by direct or indirect actions using opioids or alpha-2 adrenoceptor agonists.

Wound infiltration with local anesthetic

Patients recurrently complain of pain at the site of superficial injury, i.e. at the skin incision site. Local anesthetic infiltration of the surgical site may reduce this. A number of approaches have been shown reduce postoperative analgesia requirements including: infiltration into the subfacial parietal peritoneum, subcutaneous infiltration and field block, intraarticular injection, drains lavage etc. Wound infiltration is a safe, simple, effective and under-utilized postoperative analgesic technique.

Non Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents (NSAIDS).

Non steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS) have been used for some time in ambulatory surgery to reduce the dose of opioid required for pain relief, with the potential for less nausea, vomiting and sedation. NSAIDS act peripherally to inhibit the cyclo-oxygensase enzymes responsible for production of pro-inflammatory mediators at the site of injury. The major therapeutic limitation of using these agents is the delay between application and onset time, because of peripheral action, as compared with opioids. In order to attain full efficacy, it is essential to give NSAIDS at induction or early during the procedure. NSAIDS, whether COX-1 or COX-2 inhibitors, are equally efficacious in terms of pain relief but their clinical applications are limited by concerns relating to gastric bleeding, renal impairment and platelet dysfunction.2 In general NSAIDS should be avoided in patients that have undergone mucosal surgery (such as resection of the nasal mucosa), intracranial surgery, some spinal surgeries and operations in which a cross-clamp has been placed on the aorta (abdominal aortic aneurysm repair for example). In addition, patients with known renal dysfunction are at risk of acute renal failure, and NSAIDS should be withheld.

NSAIDS may be administered by a variety of routes including oral, intravenous, intramuscular, and rectal. Agents routinely utilized in the operating room and PACU include ketoralac, diclofenac and tenoxicam. There is a considerable body of evidence supporting the use of NSAIDS as adjunct analgesic agents.2;8;24 For example, ketoralac 30mg has equipotent analgesic effect to morphine 10mg. Where possible patients should be administered NSAIDS in the operating room or PACU.

Regional anesthetic techniques

A multitude of different regional anesthetic techniques has been used for surgery. These are frequently combined with general anesthesia to ensure absence of pain in the postoperative period. For example, paravertebral block has emerged as an effective option for breast surgery in addition to general anesthesia.25 Combinations of ileoinguinal and ileohypogastric nerve blockade and caudal block, have been shown to significantly reduce postoperative pain in children and adults following inguinal hernia repair.26 The commonly used regional nerve blocks are featured in Table 5.

| Table 5 Regional Blocks that may reduce Postoperative Pain |

| Block Type |

Indication |

| Upper-limb blocks: |

|

| Bier’s block |

Surgery to hand or wrist (e.g. Colles’ Fracture) |

| Digital Nerve Block |

Surgery to finger |

| Wrist Block: median, ulnar and radial nerves |

Surgery to hand |

| Elbow Block: median, ulnar and radial nerves |

Surgery to hand or wrist |

| Brachial Plexus Block: |

|

| Axillary Approach |

Surgery to hand, wrist or lower arm |

| Supra-calvicular Approach |

Surgery to hand, wrist, upper and lower arm |

| Interscalene Approach |

Surgery to upper limb and shoulder |

| Neuraxial Blocks: |

|

| Spinal |

Surgery to lower extremities |

| Epidural |

Surgery to lower extremities, abdomen, thorax |

| Caudal |

Surgery to perinuem (e.g. hemmoroidectomy) |

| Paravertebral Block |

Thoracic and abdominal surgery (e.g. breast surgery, herniorrhaphy). |

| Lower-limb Blocks: |

|

| Sciatic Nerve Block |

Surgery to lower limb |

| Obturator Nerve Block |

Surgery to lower limb |

| 3-in-1 (Lumbar Plexus) Block |

Surgery to lower limb |

| Knee Block: common peroneal, tibeal & saphenous |

Surgery to lower leg |

| Ankle Block |

Surgery to foot |

| Truncal Blocks |

|

| Intercostal Blocks |

Thoracic surgery |

| Inguinal Field Blockade |

Surgery in lower abdomen (e.g. hernia repair) |

| Penile Block |

Surgery to penis (e.g. circumcision) |

Alpha-2 receptor agonists.

The alpha2 -agonists clonidine and dexmedetomidine have been reported to provide effective analgesia following a variety surgical procedures and when given by oral, intrathecal and intravenous routes of administration.

In general, alpha 2 -agonists are best used as adjuncts with other analgesics to minimize the side effects of sedation and hypotension. Clonidine, when given orally as a premedication (5 mg/kg), reduces morphine PCA requirements by 37% and significantly reduces the incidence of nausea and vomiting.27 When added to local anaesthetics, clonidine has been shown to augment the effectiveness and duration of action of peripheral nerve blocks.28

Paracetamol/Acetaminophen

Paracetamol is an agent commonly used in multimodal techniques, due to its wide availability and low side effect profile in therapeutic dosage. Oral and rectal acetaminophen, as an adjunct to opioids, reduces pain scores by 20% – 30%.29 It has analgesic and antipyretic, but not anti-inflammatory, activity. Although the mechanism of action of acetaminophen is poorly understood, it is believed to act by the inhibition of the COX-3 isoenzyme and subsequent reduced prostanoid release in the central nervous system. In addition, there is some suggestion that it acts on the opioidergic system and NMDA receptors. Acetaminophen is a weak analgesic agent and has little or no anti-inflammatory activity. Thus it has no role as monotherapy-analgesia following major surgery. Nevertheless, there is abundant evidence that acetaminophen significantly enhances analgesia when combined with opioids and NSAIDS. It has little or no impact on the gastrointestinal tract or kidney. However, in high dosage acetaminophen may cause irreversible liver damage. This agent is strongly recommended for balanced analgesia in perioperative patients.

3. Differential diagnosis / Work the problem

What is the differential diagnosis?

An agitated patient, emerging from anesthesia, is in pain until otherwise proven (figure 4). It is imperative to assess the patient’s respiratory status to ensure that he is oxygenating and ventilating as hypoxemia and hypercarbia may manifest as agitation. The patient’s agitation should also be assessed in terms of their total physical status: in general agitation plus tachycardia and hypertension suggests hyperadrenergic activity (stress), and agitation associated with bradycardia suggests increased vagal activity. This can result, for example, from distress associated with a full bladder.

Postoperative patients that are agitated and tachycardic may have partial neuromuscular blockade (chapter 4: hypertension and tachycardia). Other potential diagnoses include drug withdrawal (beta blockers, clonidine, alcohol, cocaine and amphetamines), drugs (atropine, neostigmine, naloxone or flumazenil) and pathologic processes (neurologic injury, electrolyte abnormalities and endocrinopathy). Neurologic injuries include ermergence delirium, stroke, intracranial bleed, raised intracranial pressure and transcranial herniation. Electrolyte abnormalities that may cause agitation include hypernatremia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypophosphatemia, hypercalcemia and hypomagnesemia). Endocrinopathies that may cause agitation include thyrotoxicosis, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypoglycemia, pheochromocytoma and carcinoid syndrome.

Figure 4: Managing the Agitated Patient

Common things are common – once life threatening causes of agitation have been outruled, one must address pain.

The clinical assessment of pain, analgesia, anxiety and sedation require quantification, hence the use of scoring systems. The behavioral pain score was discussed in chapter 4; it allows the bedside clinician determine whether or not the sedated patient is in pain. In this scenario the patient is agitated, and the level of agitation should be assessed using an alternative system, such as the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS table 6).30 This tool allows the clinician to assess whether the patient is agitated or sedated using a + (plus) score for agitation and a minus (-) score for sedation. It then allows for titration of sedative drugs. The scale scores the patient from -5 (comatose) to +4 (combative, as in this case).

Visual Analog Scale for Pain

No Pain Mild Pain Moderate Pain Severe Pain Worst

_____________________________________________________________________

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

|

Figure 5: Visual Analog Scale

Once the patient is co-operative, pain should be assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS figure 6).31;32 This is a 0-10 scoring system in which 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain the patient has ever experienced. The goal is to obtain a pain score of 3 or less or pain that is considered acceptable by the patient.33 Occasionally the patient may report a higher score than would be suspected by physiologic data, and the bedside nurse is required to make an objective decision about the need for further analgesia.

|

Table 6 Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale

|

| Clinical Status |

RASS

|

| Combative (violent dangerous to staff) |

4

|

| Very agitated (pulling on or removing catheters) |

3

|

| Agitated (fighting ventilator) |

2

|

| Anxious |

1

|

| Spontaneously alert calm and not agitated |

0

|

| Able to maintain eye contact >= 10 seconds |

-1

|

| Able to maintain eye contact < 10 seconds |

-2

|

| Eye opening but no eye contact |

-3

|

| Eye opening or movement with physical or painful stimuli |

-4

|

| Unresponsive to physical or painful stimuli (deeply comatose) |

-5

|

4. Solve or resolve the problem

Step 1: Ensure that the airway is patent and that the patient is breathing spontaneously. Apply supplemental oxygen. Ensure that the patient has iv access and that intravenous fluid is running. Check the patient’s pulse and blood pressure. Position the patient in the semi-recumbent position.

Step 2: Score the patient’s agitation/pain using RASS and VAS

Step 3: Commence the opioid titration protocol (figure 6).34;35 The choice of agent, morphine or hydromorphone is determined by the clinician – if the patient is to receive a morphine PCA they should receive bolus morphine, a hydromorphone PCA – bolus hydromorphone etc. The dose should be adjusted for the patient’s weight.

Step 4: The goal of the opioid titration protocol is to aggressively treat pain by assessing the patient’s pain score,33 and to prevent oversedation by using the RASS score.

Step 5: If the patient remains agitated despite significant opioid administration, consideration should be given to anxiety and delirium. Delirium is defined as an acute disturbance of consciousness (reduced clarity of awareness of the environment) and cognition with reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention. The patient may be disorientated in time, place or person. If the patient is orientated, anxiety may be a problem, and this can be managed with judicious administration of midazolam 1-2mg iv. Anxiolytics should not be administered before analgesics in the agitated postoperative period unless the significant consideration has been given to pain as the etiology of the problem.

Step 6: If the patient is complaining of severe intractable pain, out of proportion to the injury and unresponsive to analgesia and anxiolysis, consideration should be given to an surgical problem. For example, in a patient that has had orthopedic surgery to the leg, severe pain may signal a compartment syndrome: the patient has ischemic pain. If a surgical cause had been discounted, consideration should be given to a regional anesthetic approach (epidural, brachial plexus catheter etc) or to the addition of ketamine to the PCA.

Step 7: If the patient becomes oversedated (RASS -3 or below) as a result of narcosis (associated with bradypnea), opioid administration should be discontinued until the RASS score is -2 or above. In extreme cases, where the patient is comatose and hypoventilating, naloxone should be administered in aliquots of 40mic/g, until the RASS is -2 or above. It is essential that the clinician consider alternative causes of coma, such as stroke, brain hemorrhage or intracranial hypertension).

Figure 6: Management of Patient in Pain or Agitated

Conclusions

- Pain is now considered the “fifth vital sign”.

- Postoperative patients that are agitated should be considered to be in pain until otherwise proven.

- Pain is a multisystem problem that manifests as an emotional response to a noxious stimulus. Pain starts at the nocioceptor and is amplified by local inflammatory mediators and spinal cord windup leading to central and peripheral sensitization. In addition, pain activates the hypothalmo-pituitary-adrenal axis leading to anxiety and diaphoresis.

- Pain should be managed by a multimodal approach that addressed the problem at different levels in the pain pathways.

- Opioid agents remain the mainstays of management of pain. Of these morphine and hydromorphone are the most popular and effective agents for managing visceral pain in PACU.

- Opioids should be titrated using an opioid titration protocol, that scores both pain and sedation.

- Anxiety, delirium and surgical problems may worsen pain, and should be addressed by the clinician.

- Pain that is unresponsive to aggressive and analgesic therapy should prompt the clinician to consider a surgical cause.

This PBLD was written by Patrick Neligan Version 1.3 September 2007

References

1. Myles PS, Williams DL, Hendrata M, Anderson H, Weeks AM: Patient satisfaction after anaesthesia and surgery: results of a prospective survey of 10,811 patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2000; 84: 6-10

2. Joshi GP: Multimodal analgesia techniques and postoperative rehabilitation. Anesthesiol.Clin.North America. 2005; 23: 185-202

3. Kehlet H, Dahl JB: The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth.Analg. 1993; 77: 1048-56

4. Kehlet H: Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br.J.Anaesth. 1997; 78: 606-17

5. White PF, Kehlet H, Neal JM, Schricker T, Carr DB, Carli F, the Fast-Track Surgery Study Group: The Role of the Anesthesiologist in Fast-Track Surgery: From Multimodal Analgesia to Perioperative Medical Care. Anesthesia Analgesia 2007; 104: 1380-96

6. Brennan TJ, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM: Mechanisms of incisional pain. Anesthesiol.Clin.North America. 2005; 23: 1-20

7. Cohen MJ, Schecter WP: Perioperative pain control: a strategy for management. Surg Clin.North Am. 2005; 85: 1243-57, xi

8. Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ: Pain mechanisms and management: an update. Clin.Exp.Pharmacol.Physiol 1995; 22: 679-88

9. Woolf CJ: Central sensitization: uncovering the relation between pain and plasticity. Anesthesiology 2007; 106: 864-7

10. Wolpaw JR, Tennissen AM: Activity-dependent spinal cord plasticity in health and disease. Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 2001; 24: 807-43

11. Herrero JF, Laird JM, Lopez-Garcia JA: Wind-up of spinal cord neurones and pain sensation: much ado about something? Prog.Neurobiol. 2000; 61: 169-203

12. Murray A, Hagen NA: Hydromorphone. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2005; 29: 57-66

13. Stanley TH: Fentanyl. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2005; 29: 67-71

14. Desmeules JA: The tramadol option. Eur.J Pain 2000; 4 Suppl A: 15-21

15. Lehmann KA: Recent Developments in Patient-Controlled Analgesia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2005; 29: 72-89

16. Ballantyne JC, Carr DB, Chalmers TC, Dear KB, Angelillo IF, Mosteller F: Postoperative patient-controlled analgesia: meta-analyses of initial randomized control trials. J Clin.Anesth 1993; 5: 182-93

17. Dolin SJ, Cashman JN, Bland JM: Effectiveness of acute postoperative pain management: I. Evidence from published data. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2002; 89: 409-23

18. Werawatganon T, Charuluxanun S: Patient controlled intravenous opioid analgesia versus continuous epidural analgesia for pain after intra-abdominal surgery. Cochrane.Database.Syst.Rev. 2005; CD004088

19. Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, Tramer MR: Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. A quantitative systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol.Scand. 2001; 45: 795-804

20. Hudcova J, McNicol E, Quah C, Lau J, Carr DB: Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus conventional opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane.Database.Syst.Rev. 2006; CD003348

21. Macintyre PE: Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: one size does not fit all. Anesthesiol.Clin.North America. 2005; 23: 109-23

22. Owen H, Plummer JL, Armstrong I, Mather LE, Cousins MJ: Variables of patient-controlled analgesia. 1. Bolus size. Anaesthesia 1989; 44: 7-10

23. Macintyre PE: Safety and efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2001; 87: 36-46

24. White PF: The Changing Role of Non-Opioid Analgesic Techniques in the Management of Postoperative Pain. Anesthesia Analgesia 2005; 101: S5-22

25. Karmakar MK: Thoracic paravertebral block. Anesthesiology 2001; 95: 771-80

26. Nehra D, Gemmell L, Pye JK: Pain relief after inguinal hernia repair: a randomized double-blind study. Br.J.Surg. 1995; 82: 1245-7

27. Park J, Forrest J, Kolesar R, Bhola D, Beattie S, Chu C: Oral clonidine reduces postoperative PCA morphine requirements. Can.J.Anaesth. 1996; 43: 900-6

28. Eisenach JC, De Kock M, Klimscha W: alpha(2)-adrenergic agonists for regional anesthesia. A clinical review of clonidine (1984-1995). Anesthesiology. 1996; 85: 655-74

29. Schug SA, Sidebotham DA, McGuinnety M, Thomas J, Fox L: Acetaminophen as an adjunct to morphine by patient-controlled analgesia in the management of acute postoperative pain. Anesthesia Analgesia 1998; 87: 368-72

30. Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, Francis J, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, Sessler CN, Dittus RS, Bernard GR: Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA 2003; 289: 2983-91

31. Bodian CA, Freedman G, Hossain S, Eisenkraft JB, Beilin Y: The Visual Analog Scale for Pain: Clinical Significance in Postoperative Patients. Anesthesiology 2001; 95: 1356-61

32. Aubrun F, Hrazdilova O, Langeron O, Coriat P, Riou B: A high initial VAS score and sedation after iv morphine titration are associated with the need for rescue analgesia. Can.J Anaesth. 2004; 51: 969-74

33. Aubrun F, Langeron O, Quesnel C, Coriat P, Riou B: Relationships between measurement of pain using visual analog score and morphine requirements during postoperative intravenous morphine titration. Anesthesiology 2003; 98: 1415-21

34. Aubrun F, Monsel S, Langeron O, Coriat P, Riou B: Postoperative titration of intravenous morphine. Eur.J Anaesthesiol. 2001; 18: 159-65

35. Aubrun F, Monsel S, Langeron O, Coriat P, Riou B: Postoperative titration of intravenous morphine in the elderly patient. Anesthesiology 2002; 96: 17-23

This Article Copyright Patrick Neligan MA MB FCAI DIBICM 2007-2012. Neither text nor illustrations are to be used without permission.