I receive a lot of emails from confused doctors regarding the modern (Stewart) approach to acid base chemistry.

I receive a lot of emails from confused doctors regarding the modern (Stewart) approach to acid base chemistry.

A common question relates to the relative quantity of hydrogen/hydronium and hydroxyl ions. For example, if chloride is dissolved in water there is a net increase in hydrogen and a net decrease in hydroxyl. Where does the hydroxyl go?

Another question is: why if the pH of NaCl 0.9% solution 5.5 when the SID (Strong Ion Difference) is 0? Finally everyone is confused about contraction alkalosis and dilutional acidosis.

This post will attempt to explain these phenomena. I make no attempt here to explain the basics of acid base chemistry. For this read my chapters in Miller’s Textbook of Anesthesia or Longnecker’s Anesthesiology.

Acids versus Bases

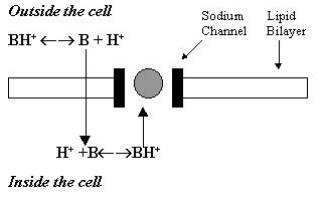

Stewart utilized the Arrhenius theory of acid base: you put chloride into water, water dissociation changes to maintain electrical neutrality releasing hydrogen ions and the solution becomes acidic. In this way chloride delivers a hydrogen ion to the solution and Chloride is an acid. This may appear confusing (where does the OH– go if H+ is delivered to the solution), but if you read below, the answer is really simple. Stewart’s approach is entirely consistent with Bronsted-Lowry, but heavily emphasizes strong ions and weak anions as the independent variables. Water is a dependent variable, as is HCO3–.

It is best to describe water as an amphiprotic molecule – simply it can be an acid or a base – a proton donor or a proton acceptor. H2O (acid) + H2O (base) ≤-≥ H3O+ + OH–

The tendency for water to dissociate into its component parts is governed by the Kw’ – the autoproteolysis constant for water:

Kw = (H3O+ ) a(OH–)

So water can act as an acid or a base depending on what is dissolved in it. We tend to get a little hung up on which is the acid and which is the base depending on how you look at it: in our teaching Chloride is functionally an acid. A lot of people think it is a base. The following my clarify your thinking:

An example – if HCl is dissolved in water:

HCl + H2O <-> H3O+ + Cl–

In this situation water acts as a conjugate base – a proton acceptor. Note that there is no net generation of OH– as the proton donor was Chloride.Likewise, if you dissolve NaOH into water

NaOH + H2O <-> Na+ +H2O + OH–

So water in this situation acts a conjugate acid, a proton donor – the conjugate acid of a strong base. Whenever, in physiology, you have a strong anion you have a conjugate acid (Hn+); whenever you have a strong cation, you have a conjugate base (OH‑). In mass conservation, each time you lose a Cl- you lose its accompanying Hn+. What Stewart emphasizes is that it is not the loss of the proton that is the problem – the supply is potentially unlimited, it is the loss of the electrolyte. The major teaching point in Stewart is that NaCl is not Na+ + Cl– (in other words the charge on sodium is balanced by the charge on chloride) rather it is NaOH + HCl.

Remember the pKa = pH + pOH

Now, if you come along and make up a solution of NaOH + HCl + H2O (normal saline), what happens?

NaOH + HCl + H2O <-> Na+ + OH– + H3O+ + Cl–

But it is not a simple as that – because HCl is a much stronger acid than NaOH is a strong base. Hence, due to their differing pKas, HCl generates more H+ than NaOH generates OH– (it has a steeper titration curve). The result, in a bag of fluid is a pH of 5.5. However, the SID is 0 – so I don’t know if the differing titration curves for HCl versus NaOH contributes somewhat to the acidifying effect of NaCl.

This last point is important – even if charges are balanced, there may be different amounts of hydrogen and hydroxyl ions present due to the pKa of the various acids and bases.

I hope this resolves the confusion: putting chloride into a solution of water does not lead to the mysterious disappearance of OH‑. Strong ions never, ever, exist without something to balance the charge; a conjugate acid or base. Functionally H+ is actually added, but it is stirred into the aqueous stew.

Dilutional acidosis and contraction alkalosis

t is important to remember that the Stewart approach emphasizes that pH is dependent on: SID (strong ion difference), pCO2 and Atot (total weak acid-anion concentration). The assumption when one looks at changes in SID is that there are no concomitant changes in the other variables (of course there is – we may hyperventilate or hypoventilate to correct the pH) – for illustrative purposes. So, under normal circumstances, the SID is 44 mEq/L. That means that there is 44mEq/L of buffer base or weak anions (Atot) balancing the charge – phosphate, bicarbonate and protein (principally albumin) – table 2 below. It is assumed the Atot remains stable. An increase in SID – as a result of contraction – immediately induces a base excess that must be associated with an increase in OH–. This does not imply that hyroxyl ions appear and hydrogen ions disappear – they were always there – but in different concentrations. The same is the case if the system is diluted – adding free water and keeping Atot stable induces an acidosis by reducing SID.

For example: construct a liquid that starts with 15 liters of water and add 2.1M of NaOH (140mmol/l) of NaOH and 1.5M of HCl (100mmol/L). This is obviously a highly alkaline solution as there is an excess of 40mmol/L of OH– (40mmol). If you add 3 liters of water to this the concentration of Na+ falls to 116mmol/L (that is 116mmol/L of OH–), and the concentration of Cl– falls to 83mmol/l (that is the 83mmol/L of H+). The total amount of excess OH– over H+ has reduced – so the pH must fall.

In physiology, the 40mEq/L SID is represented by weak acids (Atot), and, other things being equal, these do not change. These are represented by A – and carry, functionally, 40mEqL of H+. So, if you do your mathematics – the total H+ concentration is 83 + 40mEq/L (123) wheras the total OH– conventration is 116mmol/L – a difference of 7.

In effect, there is a net gain of 7mEq/L of HnO+/H+, and this results in metabolic acidosis.

| Table 1 |

ECF volume |

ECF State |

[Na+] |

[Cl–] |

[OH–]* |

SID |

[Atot–]* |

pH |

|

15000 |

Normal |

140 |

100 |

40 |

40 |

40 |

7.4 |

|

| add water |

18000 |

Expanded |

116 |

83 |

33 |

33 |

40 |

<7.3 |

| remove water |

13000 |

Reduced |

161 |

115 |

46 |

46 |

40 |

>7.5 |

*Atot=OH under normal circumstances; in this illustration Atot is kept stable.

Of course, this would result in devastating acidosis if it occurred in a human. Consequently four things occur to balance this 1. K+translocates from the intracellular space. 2. Albumin also becomes diluted (ICU alkalosis). 3. HCO3– combines with the now abundant H+ ions forming carbonic acid. 4. CO2 is blown off due to a fall in the pH of CSF.

On the face of it, this would appear to be the classic approach to ABB – but it is not. The classic approach suggests that the fall in HCO3– is due to dilution, in the Stewart approach the fall is due to consumption – as a buffer. Inevitably, as the negative charge carried by HCO3– falls, there is a dual effect – yes it represents buffering, but the charge differential between SID and Atot (buffer base or weak acids) falls, and the pH normalizes.

Does the HCO3– become diluted just like NaCL? Maybe, I’m not sure: remember HCO3– is part of a different control system. Also, as the pH falls, being weak acids, the acidic effect of bicarbonate, albumin and phosphate increases.

| Table 2: Buffer Base | |

| Buffer Base Plasma (Atot) | Buffer Base Whole Blood (Atot) |

| HCO3 24mEq/L

PO4 1 mEq/L Albumin 17mEq/L |

HCO3 20mEq/L

PO4 0.5mEq/L Albumin 9.5mEq/L Hemoglobin 18mEq/L |

What about contraction alkalosis? Take our 15L ECF and remove 2L of water – no change in quantity of Na, Cl or the concentration of buffer base (weak acid). The sodium concentration increases to 161mEq/L (OH- is the same); the chloride concentration increases to 115mEq/L. The SID is now 46mEq/L. Other things being equal the BB/Atot is 40mEq/L – so there is now an excess of 6mEq/L of OH– compared with before: metabolic alkalosis. Interestingly, universally, the HCO3– increases by a more or less similar amount. This is where Stewart’s original work is really weak – why? Either we generate more bicarbonate due to hypoventilation – slow – or else the bicarbonate becomes concentrated like everything else. Whatever way you look at it, the increasing bicarbonate functionally buffers the alkalosis (it being a weak acid – an anion).

There are lots of potential in vitro lab or in vivo animal studies that could be carried out to actually iron out exactly what goes on. I would imagine that if you took an animal, tied off the renal arteries, put in an arterial line – administered a load of water and checked the full spectrum of labs before and after you could once and for all answer this question.

I have found, over the years, that the most comfortable place to sit is in between the extremes of the Stewart and traditional approaches. I believe that Stewart was wrong about bicarbonate – it is far more important that he gave credit for, and while not a component of SID – and probably not an independent variable, it is a major player in acid base chemistry.

Is there a pool of hydrogen and hydroxyl ions that appear and disappear depending on the SID, Atot and pCO2? Yes of course there is – water exists as big blobs that exhibit either a positive or negative charge (HnO+ or HOn–). The totality of charge exhibited depends on the milieu – but really it is charge that is added alongside electrolytes – NaOH, for example. In addition, alterations in charge of weak acids resulting from changes in pH is probably more important than currently recognized (in other words Atot becomes more acidic with acid and less acidic with alkali – due to the proximity of pKa to pH 7.4 – more acidic more ionized, less acidic less ionized).

This article is entirely the work of Patrick Neligan MB FCAI FJFICM. It is not to be reproduced without permission. It is for educational purposes only. © PJN 2011