You may recall a movie from a few years ago called “Super Size Me” that featured Morgan Spurlock eating nothing but McDonalds food for a month. If offered a super sized meal, he said – yes. He became lethargic, gained weight and developed a fatty liver. The message was that if you ate highly calorific fatty food, you would become seriously unhealthy. I have argued, for some time, that Morgan should go back to McDonalds for a month and eat the same food, but drink diet sodas. There is an abundance of data that the high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in US drinks defeats the normal satiety pathways, increases appetite and leads to visceral obesity and metabolic disease (don’t believe me? Click here). Sugar sweetened drinks are likely nearly as bad. I have never understood why anyone overweight would voluntarily drink sugar sweetened drinks when they can get essentially the same product calorie free (“diet” drinks). I remember American colleagues justifying this with comments like “I don’t trust aspartame” (it has been used for 40 years no evidence it causes harm to humans – click here) – the reply <but you trust HFCS! A Frankenfood>.

You may recall a movie from a few years ago called “Super Size Me” that featured Morgan Spurlock eating nothing but McDonalds food for a month. If offered a super sized meal, he said – yes. He became lethargic, gained weight and developed a fatty liver. The message was that if you ate highly calorific fatty food, you would become seriously unhealthy. I have argued, for some time, that Morgan should go back to McDonalds for a month and eat the same food, but drink diet sodas. There is an abundance of data that the high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in US drinks defeats the normal satiety pathways, increases appetite and leads to visceral obesity and metabolic disease (don’t believe me? Click here). Sugar sweetened drinks are likely nearly as bad. I have never understood why anyone overweight would voluntarily drink sugar sweetened drinks when they can get essentially the same product calorie free (“diet” drinks). I remember American colleagues justifying this with comments like “I don’t trust aspartame” (it has been used for 40 years no evidence it causes harm to humans – click here) – the reply <but you trust HFCS! A Frankenfood>.

Last week Philip Boucher Hayes presented an RTE documentary on Ireland’s dietary habits. The programme painted a nice picture of how today’s obesity epidemic is turning into tomorrow’s cancer horror story. It turns out that Irish people are among the biggest sugar consumers in Europe; we are particularly fond of chocolate: we are a nation of carb addicts. Carb addiction shares many of the traits of opioid addiction.

So those of us who have long argued that the obesity epidemic is a problem of excess carbohydrates rather than excess fat will take note of no fewer than 3 papers in this weeks New England Journal. The most interesting of the papers, which came from Holland, randomized children aged 5 to 12 to 8oz (236ml) of sugar sweetened drinks per day (link here) (we don’t know exactly what product but it was not a common brand in Ireland (company) let’s call it “sugar drink”) versus blinded administration of 8oz of calorie free drink per day (“diet drink”). Thats it. They started with 641 normal weight children. 18 months later the children given the sugar drink had gained, on average, 1kg more in weight (2.2 pounds) compared with the other group. Children in the sugar drink group were pudgier (skinfold-thickness measurements, waist-to-height ratio, and fat mass).

So, sugar-drinks make you fat, and diet-drinks probably don’t. But what if we have been drinking sodas for years, are overweight and decide to quit? A second study, of adolescents, conducted in the USA (click here), randomized 224 adolescents (overweight/obese) to a programme (1 year) that involved giving up sweetened-sodas (HFCS). At 1 year there was a 2kg difference in weight and a significant difference in BMI between the 2 groups. This had disappeared at 2 years. In other words, presumably, they started drinking sodas again.

What about that skinny guy that you know who drinks 5 cans of Coke a day. It turns out that if you are genetically predisposed to becoming obese (your parents are overweight) then you are more likely to suffer the adipogenic effects of sweetened sodas (click here). In other words, if you have a belly, don’t give your kids sugar cola – ever. Don’t start them drinking sodas. Don’t buy sodas.

So here is the issue – they have banned smoking just about everywhere (including potentially in your own car if your children are present), based on very questionable evidence that secondary inhalation of (“passive”) smoke injures you. These data represent clear evidence of the dangers associated with a series of food products with no nutritional value that have a ready made replacement (diet soda) made by the same manufacturers. Shouldn’t we be banning the sale and administration of sugar-sodas to children (I was horrified to hear in the RTE documentary that babies at 6 months were being give carbonated drinks)? Read here to enjoy a wonderful discussion of this topic.

Now if they could only come up with diet pizza, diet chips and diet scones……

Author Archives: Pat Neligan

Don’t Understand Balloon Pumps – don’t bother

Alas – another intervention bites the dust. For decades the intra-aortic balloon pump has been heralded as the great savior of the patient with cardiogenic shock. If you have always found these devices confusing (when to use, when to wean, what difference 1:1 versus 1:2 augmentation etc), then worry not: they are heading to the Swan Ganz junkyard. In this week’s NEJM the IABP-SHOCK II trial is published (read here). Six hundred patients were recruited in 37 locations in Germany in 3 years – randomized to IAB-counterpulsation at 1:1 or control, essentially catecholamine, therapy. Patients were eligible for the trial if they had had any form of myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock, or needed an emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. The majority of patients had PCIs and the IABP could be placed before or after.

Alas – another intervention bites the dust. For decades the intra-aortic balloon pump has been heralded as the great savior of the patient with cardiogenic shock. If you have always found these devices confusing (when to use, when to wean, what difference 1:1 versus 1:2 augmentation etc), then worry not: they are heading to the Swan Ganz junkyard. In this week’s NEJM the IABP-SHOCK II trial is published (read here). Six hundred patients were recruited in 37 locations in Germany in 3 years – randomized to IAB-counterpulsation at 1:1 or control, essentially catecholamine, therapy. Patients were eligible for the trial if they had had any form of myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock, or needed an emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. The majority of patients had PCIs and the IABP could be placed before or after.

There is a widespread belief that using IABP improves pump function, restoring cardiovascular health and preventing the development of multi-organ failure. The primary endpoint of the study was 30 day all cause mortality. This is a flawed measure in critical care, as many patients will still be alive at 30 days, awaiting withdrawal of life sustaining therapy. The authors are in the process of collecting 90 day and 6 month data. The authors also looked for evidence of multi-organ failure (using SAPS II), infectious and ischaemic (using lactate) complications.

Previous studies have reported mortality rates of 42-48% in cardiogenic shock. The authors reported 30 day mortality of 39.7% in the IABP group and 41.3% in the control group (not significant). There was no significant difference in any of the other endpoints either..

Criticisms and generalizability? The mortality rate was lower than expected, but this was a heterogenous German population, a single health system, with an average BMI of 27. So maybe the patients were less unhealthy than comparable North American Studies. More likely, the IABP can be added to a long list of devices that receive religious like devotion, but have little clinical benefit. Further data of interest would be whether or not IABP really benefits postoperative cardiac patients. In the meantime, it is likely that we will encounter these devices less frequently in the future.

Giving up Colloid? – Yes we can!

Colloid lovers are distraught by the publication of the 6S study from Scandanavia, which has demonstrated that hydroxy ethyl starches (HES) were associated with poor outcomes (read here). For many of us, however, colloids are like nicotine, caffeine, carbohydrates and heroin rolled into one: we just believe in them. It’s so hard to stop. This month in Critical Care Medicine, a German hospital critical care group proved that you could – quit! (read here – subscription required)

Colloid lovers are distraught by the publication of the 6S study from Scandanavia, which has demonstrated that hydroxy ethyl starches (HES) were associated with poor outcomes (read here). For many of us, however, colloids are like nicotine, caffeine, carbohydrates and heroin rolled into one: we just believe in them. It’s so hard to stop. This month in Critical Care Medicine, a German hospital critical care group proved that you could – quit! (read here – subscription required)

In the Jena intensive care unit, over a 6 year period, clinicians initially used HES, gelatin and crystalloid, then gelatin and crystalloid and ultimately crystalloid only. Bayer and colleagues looked at CVP changes, SvO2, lactate normalisation, normalisation of MAP and discontinuation of vasopressors – comparing each phase against each other. In the first instance, CVP increased faster with colloids than crystalloids, which would be terrific if anyone had ever shown that rapidly increasing CVP improved outcomes. It doesn’t. In fact CVP is next to useless (if you don’t believe me – read this). Fluids are administered to reverse shock, and in each of the phases colloids had no appreciable benefit. Indeed, the amount colloid versus crystalloid was revealing: for HES it was 1:1.4 (HES vs Crystalloid i.e. 700ml Lactated Ringers versus 500ml HES 130/0.4); for gelatin it was 1:1.1 (i.e. 550ml LR versus 500ml gelatin). So there was little, if any, colloid effect. Moreover, patients in the crystalloid group mobilised fluid earlier than those in the colloid group.

So, colloids had no beneficial effect. What about harm? There was more acute kidney injury, worsened renal indices and longer continuous renal replacement therapy in the colloid group. Finally, patients who received colloids spent longer on mechanical ventilators than patients who received crystalloids.

It could be argued that this cohort study was flawed in that, as medicine advance, outcomes necessarily improve. So the newest patients should have had the best outcomes. However, there is no evidence that critical care outcomes are better now than 7 or 8 years ago, nor has the clinical practice move on significantly. From my perspective these data are valid, and may provide a roadmap to navigating ourselves away from the crutch and clutch of colloids.

EuSOS study published – and it’s not pretty!

![]() 46,539 patients from all over Europe were recruited to the The European Surgical Outcomes Study over 7 days in April 2011 (read here). Day cases, cardiac and neurosurgical patients were excluded. The overall mortality rate was 4% (nearly 1 in 20 patients). 8% of patients were admitted to ICU or HDU at some stage – but, astonishingly, 73% of those who died never saw a critical care practitioner.

46,539 patients from all over Europe were recruited to the The European Surgical Outcomes Study over 7 days in April 2011 (read here). Day cases, cardiac and neurosurgical patients were excluded. The overall mortality rate was 4% (nearly 1 in 20 patients). 8% of patients were admitted to ICU or HDU at some stage – but, astonishingly, 73% of those who died never saw a critical care practitioner.

For Ireland 856 patients were recruited into the study; 66 went to critical care beds postoperatively. Median hospital stay was 3 days (1.0-6.0). 6.4% died in hospital, with an unadjusted (for severity of illness) odds ratio of death (compared with the UK) of 1.86. When severity of illness was taken into account the OR of death was 2.61. This puts us down the scale of outcomes with Croatia, Slovakia (better), and Romania and Latvia (marginally worse).

What is truely frightening about these data – is that the reference country, the UK, aside from having a similar population to ours, had worse outcomes than they had expected (mortality 3.6% rather than the predicted 1.6%).

It could be argued that these data are skewed by relatively low numbers, recruitment exclusively in academic medical centers (private hospitals cherry pick the healthiest elective surgery patients), the significant limitations of the ASA physical status grade (between 2 and 3 there really should be 3 more grades – clinicians may have also reported patients as a ASA-PS 2 when they really were a 3), reporting bias etc. Alternatively, our patients might do badly because of weaker nursing care at ward level and fewer critical care beds per head of population.

If the anaesthesia and critical care community in Ireland wants to look into this further, perhaps a worthwhile study would be an enthusiatic clinician to pull out the charts of all 856 patients and figure out why Ireland did so badly. Comments?

Hydroxy Ethyl Starches – are we nearing the end of the road?

When the VISEP study was published in 2008,1 proponents of colloid based resuscitation (myself included) argued that, since the study was conducted using old generation pentastarches, the data were not generalizable to all hydroxyl-ethyl fluids.2 Indeed there was an emerging body of evidence supporting the safety of newer, lower molecular weight starches; particularly those composed of balanced salt solutions. Since the mind boggling revelations about the potential scale of academic misconduct by Joachim Boldt,7 with a large number of his publications now expunged, we have all become somewhat anxious about the true safety of HES compounds. The answer is now here, following the publication of the 6S study from Scandanavia.6

When the VISEP study was published in 2008,1 proponents of colloid based resuscitation (myself included) argued that, since the study was conducted using old generation pentastarches, the data were not generalizable to all hydroxyl-ethyl fluids.2 Indeed there was an emerging body of evidence supporting the safety of newer, lower molecular weight starches; particularly those composed of balanced salt solutions. Since the mind boggling revelations about the potential scale of academic misconduct by Joachim Boldt,7 with a large number of his publications now expunged, we have all become somewhat anxious about the true safety of HES compounds. The answer is now here, following the publication of the 6S study from Scandanavia.6

Colloid fluids have one purpose – to reduce the volume of fluid required to achieve hemodynamic goals. There is something of a transatlantic controversy – the majority of European clinicians have traditionally been colloids believers; the majority of North Americans are not. Colloids are more expensive than crystalloids, have known allergic and bleeding potential and the onus of proof is always on the intervention. Presumably, if colloids are effective, they restore the circulation rapidly, prevent organ failure, prevent fluid related morbidity (pulmonary edema, wound complications, ileus etc.), reduce the length of hospital stay and reduce mortality. If these results are not achieved then colloids are, essentially, intravenous “snake oils”. Previous literature, suggest the opposite – that HES products, in particular, are associated with allergy, renal dysfunction and bleeding. There is essentially no supportive evidence in the ICU, and evidence to support colloids in the operating room is more strongly associated with the use of devices such as esophageal Doppler to achieve resuscitation goals. 4 Nevertheless, there is an emerging consensus that fluid over-resuscitation is associated with medley complications, and that measures that restrict overall fluid volume, particularly from 8 to 72 hours following injury or surgery, may be associated with improved outcomes.3-5 Often fluid studies are single centred, compare one colloid against another, or use weak or surrogate endpoints. What we needed was a multicentre, international study, that looked at hard long term endpoints.

The Scandanavian group randomized 800 critically ill patients to a Ringer’s acetate solution that either contained 130/0.4 HES or did not.6 The patients were followed on an intention to treat basis for 90 days. Patients were enrolled if they met the criteria for severe sepsis within the previous 24 hours. Patients were given fluid by bedside clinicians in accordance with their clinical judgement (i.e. there was no fluid resuscitation protocol), and were blinded to the nature of the fluid administered. The quantity of study fluid was limited to the maximum daily dose of colloid (50ml/kg); open label Ringer’s acetate was administered if this volume was exceeded, and patients could receive saline, blood products and albumin.

This impressively simple study was conducted in 4 countries, with 50% of patients being cared for in academic medical centres and 50% in community hospitals. The study was powered to demonstrate a 10% reduction in mortality among 800 randomized patients at 90 days. What the authors demonstrated, however, was the opposite.

At 90 days following randomization, 201 of 398 patients (51%) assigned to HES 130/0.4 had died, as compared with 172 of 400 patients (43%) assigned to Ringer’s acetate (absolute risk increase of 8%, number needed to treat 12; P=0.03). In the 90-day period, 87 patients (22%) assigned to HES were treated with renal-replacement therapy versus 65 patients (16%) assigned to Ringer’s acetate (absolute risk increase of 6% NNT 16; P=0.04). The risk of bleeding did not reach statistical significance – although post hoc analysis following randomization suggests that the HES group had a greater incidence of bleeding.

Interestingly, the volume of fluid administered to each group was not different: there was not colloid-effect, no fluid sparing. This was consistent with the findings of the VISEP trial.2 Although a significant proportion of both groups received blood products or albumin, there was no statistical significance between the groups. In fact, the only difference between the groups was whether or not HES was administered; patients that received HES 130/0.4 were more likely to die or have kidney injury.

At this point in time the weight of evidence is now stacked up against the use of HES solutions in critical illness; the use of these agents in septic shock cannot be justified.

References

1. Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N et al. Intensive Insulin Therapy and Pentastarch Resuscitation in Severe Sepsis. N Engl J Med 2008;358(2):125-139.

2. Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N et al. Intensive Insulin Therapy and Pentastarch Resuscitation in Severe Sepsis. N Engl J Med 2008;358(2):125-139.

3. Kehlet H, Bundgaard-Nielsen M. Goal-directed Perioperative Fluid Management: Why, When, and How? Anesthesiology 2009;110(3).

4. Lubarsky DA, Proctor KG, Cobas M. Goals Neither Validated Nor Met in Goal-directed Colloid versus Crystalloid Therapy. Anesthesiology 2009;111(4).

5. Nisanevich V, Felsenstein I, Almogy G, Weissman C, Einav S, Matot I. Effect of Intraoperative Fluid Management on Outcome after Intraabdominal Surgery. Anesthesiology 2005;103(1).

6. Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, Tenhunen J, Klemenzson G, +àneman A et al. Hydroxyethyl Starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer’s Acetate in Severe Sepsis. N Engl J Med 2012;367(2):124-134.

7. Shafer SL. Shadow of Doubt. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2011;112(3):498-500.

This article is copyrighted by Patrick Neligan 2012 please do not reproduce without permission

Anaesthesia Ireland – present tense, future – bright but scary

Run through training at last – this will guarantee a bright future for our specialty and correct the wrongs of a previous generation. But some questions must be asked. This process may open a Pandora’s box regarding anaesthesia staffing around the country and may ultimately hasten the implementation of a sub consultant grade.

In the late 1990s the Specialist Registrar System (SRP) was introduced – and it ambushed the Department of Health. They could not distinguish SPR from senior registrar (SR) with the result that trainees essentially went from SHO to SR salaries, they received SR contracts and started looking for non clinical days in addition to study leave. Softened up by higher incomes and the removal of the SR bottleneck, trainees were bamboozled into significant changes in training. The first was the 7 year rule – a minimal of 7 years of training. The logic behind this was the UK trainees were quoted as stating that they “didn’t feel that they were ready for consultancy after 6 years” [nobody bothered to ask the Irish trainees – but we told them anyway that we disagreed]. This was a patent absurdity – all Irish graduates went on to do fellowships abroad at that stage, so training time was at least 8 years plus a year in the doldrums if you failed your primary or didn’t accrue sufficient brownie points to get into the SPR system. As a hedge, the College, then in it’s infancy, introduced the “year 3 out” system: you could take a year off at year 3 SPR and do a fellowship then; of course you had to be back in a year to recommence your training. It was inevitable that this would leave a huge hole in training numbers – year out trainees couldn’t be replaced – there would be empty slots. Would anybody be back within a year? Unsurprisingly, chaos followed. Hospitals never knew from one 6 month period to the next whether or not they would be getting a full compliment of SPRS.

In the late 1990s the Specialist Registrar System (SRP) was introduced – and it ambushed the Department of Health. They could not distinguish SPR from senior registrar (SR) with the result that trainees essentially went from SHO to SR salaries, they received SR contracts and started looking for non clinical days in addition to study leave. Softened up by higher incomes and the removal of the SR bottleneck, trainees were bamboozled into significant changes in training. The first was the 7 year rule – a minimal of 7 years of training. The logic behind this was the UK trainees were quoted as stating that they “didn’t feel that they were ready for consultancy after 6 years” [nobody bothered to ask the Irish trainees – but we told them anyway that we disagreed]. This was a patent absurdity – all Irish graduates went on to do fellowships abroad at that stage, so training time was at least 8 years plus a year in the doldrums if you failed your primary or didn’t accrue sufficient brownie points to get into the SPR system. As a hedge, the College, then in it’s infancy, introduced the “year 3 out” system: you could take a year off at year 3 SPR and do a fellowship then; of course you had to be back in a year to recommence your training. It was inevitable that this would leave a huge hole in training numbers – year out trainees couldn’t be replaced – there would be empty slots. Would anybody be back within a year? Unsurprisingly, chaos followed. Hospitals never knew from one 6 month period to the next whether or not they would be getting a full compliment of SPRS.

Simultaneously, the number of anesthesia trainees in Ireland mushroomed, driven principally by the need to have an epidural service in every general hospital in the country.  Hospitals clamoured to obtain BSTs, hired lots of “non scheme” NCHDs, and loose criteria for training, the need to reduce the frequency of call and various college sponsored “programs” (7/6 etc) meant that the number of NCHDs in anesthesia in Ireland grew relentlessly over the past decade. With the bloated SPR system and light touch regulation of training, NCHDs that in the past spent most of their training time in Dublin, Cork or Galway, were now trotting up and down the country every 6 months, often on a provincial towns circuit to provide service, rather than obtaining competency based training. This led to a generation of tired, bored NCHDs, that often found it difficult to return from Australia to finish their “training”. Yes, after 7-8 years you couldn’t help but be a competent anesthetist – but it only takes 3 years in the United States.

Hospitals clamoured to obtain BSTs, hired lots of “non scheme” NCHDs, and loose criteria for training, the need to reduce the frequency of call and various college sponsored “programs” (7/6 etc) meant that the number of NCHDs in anesthesia in Ireland grew relentlessly over the past decade. With the bloated SPR system and light touch regulation of training, NCHDs that in the past spent most of their training time in Dublin, Cork or Galway, were now trotting up and down the country every 6 months, often on a provincial towns circuit to provide service, rather than obtaining competency based training. This led to a generation of tired, bored NCHDs, that often found it difficult to return from Australia to finish their “training”. Yes, after 7-8 years you couldn’t help but be a competent anesthetist – but it only takes 3 years in the United States.

Drunk on high salaries and 21st Century Irish hubris, the trainees plodded along: the Anaesthetist in Training Group – once a potent force with year reps, reps to AAGBI, IMO and GAT, became a shadow of itself (an now appears to have disbanded).* The caliber of trainees, frankly, fell – in some cases – quite sharply. In recent times, the economic crisis seems to have snapped a lot of heads into focus….

The last 12 months has seen the resurrection of Irish anaesthesia. The BST programmes have become hyper-competitive to access. The distribution of trainees has streamlined. The year out has been closed off. And now, training has been shortened to 5+1 (as opposed to 7+whatever). Five plus 1 means that you only have to do 5 years of training in Ireland: the 6 year, required for CCST, can be spent doing fellowship training abroad – assuming that your competencies are in place. In this the College is taking a calculated risk – 1. that among all of those “general” jobs around the country, the competencies are actually there, 2. with theatre closures and other austerity measures modules may suddenly evaporate, 3. senior registrars at year 5 will want to stay and do fellowships. On the surface one would assume that the more ambitious would head for the stars after 5 years – but this has not been the case in other specialties, particularly radiology, that introduced a +1 year. Do you really need to do a fellowship abroad to be an anesthetist in Ireland? No – but all of us that have travelled believe that training abroad has improved us as doctors, as people, and broadened our viewpoints.

Where are the other challenges in this system? Our specialty needs to become more family friendly – too many trainees are spending their weekends (and non clinical days I would think) criss crossing the country to spend time with loved ones and children, while exiled away from home. The re-regionalisation of training will certainly, and welcomingly, improve this. For example, trainees in the WRAT`s/SPR scheme will come to the West for 3 full years – 2 of which will be spent (one presumes) in Galway. Presumably they will then move on to Dublin and stay there for the next 2 years and decide themselves how to spend their fellowship year.

Annualised intake is going to be a problem: with staggered intake, most large hospitals had 1 or 2 beginners every 6 months, and they gradually moved onto the call system three months in. This was not problematic – now beginners will arrive once a year and there will be a lot of them. In the United States, of course, 30% of residents switched over every July – summer was a very busy time for everybody concerned, but once September came, the new residents carried a relatively greater burden of call. We really cannot do that in Ireland – particularly if the European Work Time Directive ever becomes enforced. Summer may be savagely busy for mid level trainees.

Further, there appears to be an evaporating pool of non training NCHDs in Ireland. Those that were hired from India & Pakistan during the HSEs global recruitment drive were underwhelming (to say the least) – with no obvious career plan or pathway. It has to be said – that after decades of training non EU medical graduates in anesthesia, we do have a responsibility to continue this into the future. It is inconceivable that non EU graduates will get into BST places in any quantity for the foreseeable future. So why come to Ireland at all? There is going to be an inevitable service gap in anesthesia in Ireland: who will fill the clogs of non training NCHDs in the future? Will it be nurse anesthetists (unlikely and unacceptable), nurse practitioners (certainly in pain and maybe ICU), permanent registrars (yes – they already exist and they will become more plentiful) or will they be post-CCST “specialists”?

I would hate to think that we are training a generation of talented young anesthetists to fill service level jobs in the HSE; with little career progression, subordinate to their consultant colleagues. Certainly promotional grades within the consultant body is a good idea (to prevent premature “retirement”), but the subconsultant grade is just a yellow-pack alternative. Not even the British have gone down this line. While it remains possible for our medical graduates to obtain employment in more remunerative health systems (North America, Australia, New Zealand), the Department of Health should thread lightly when dealing with future medical manpower. The current “high cost” model of consultancy is one of the great myths of Irish medicine: healthcare workers become expensive when they start getting additional payments for nights, weekends and bank holidays. Consultants provide out of hours services for very little reimbursement. Interestingly, many North American academic centers have replaced nurse anesthetists with physician anesthesiologists because, overall, they are less expensive: doctors are more flexible in terms of working hours, rest times, breaks and can do everything (a nurse cannot consent a patient for anesthesia!). The DOHC might be better of re-negotiating with the current consultant group than dumping on the specialists of the future.

I would hate to think that we are training a generation of talented young anesthetists to fill service level jobs in the HSE; with little career progression, subordinate to their consultant colleagues. Certainly promotional grades within the consultant body is a good idea (to prevent premature “retirement”), but the subconsultant grade is just a yellow-pack alternative. Not even the British have gone down this line. While it remains possible for our medical graduates to obtain employment in more remunerative health systems (North America, Australia, New Zealand), the Department of Health should thread lightly when dealing with future medical manpower. The current “high cost” model of consultancy is one of the great myths of Irish medicine: healthcare workers become expensive when they start getting additional payments for nights, weekends and bank holidays. Consultants provide out of hours services for very little reimbursement. Interestingly, many North American academic centers have replaced nurse anesthetists with physician anesthesiologists because, overall, they are less expensive: doctors are more flexible in terms of working hours, rest times, breaks and can do everything (a nurse cannot consent a patient for anesthesia!). The DOHC might be better of re-negotiating with the current consultant group than dumping on the specialists of the future.

Will the run-through training scheme produce a generation of anesthetists that are more likely than those currently finishing off their training to take “Specialist” (sub consultant) positions? You better believe it: a young doctor told day 1 that they would be guaranteed a consultant slot in 10 years – after 6 years of training and 4 years as a specialist – would jump at it [See Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (click here) – level 2 SECURITY!]. Don’t kid yourself, the majority of trainees engaging in anesthesia in 2012 will not head off to Australia or North America for 2 or 3 years, they won’t have a pile of publications when they apply for permanent positions, and they will likely, keenly, take permanent “specialist” posts.

How do we, as a fraternity combat the inevitable “dumbing down” of anesthesia:

1. We need to encourage research and academic endeavors as aggressively as we do exam preparation. Academics must be seen as a lifelong obligation – not just a box-ticking process to “get a job.”

2. There needs to be specialist pathways within the career of anesthetists: you need to decide that you are a researcher, an educator, a manager or an expert clinician. WIthout being one of the above you cannot become a consultant (as we know them today).

3. There needs to be a late training challenge: an exit exam, a thesis or the requirement to obtain an advanced degree to obtain CCST. For example – all final year SPRs might be required to submit a thesis to obtain a Masters in Anaesthesia.

4. There needs to be a secondary pathway into anesthesia in Ireland, for those that commenced training in equivalent systems abroad.

5. Fellowship training should be targeted towards need: there has been a constant stream of trainees going to Australia to become intensivists over the past decade – but where are the obstetric anesthetists, neuroanaesthetists, those that did ambulatory care, masters in education etc? If the HSE want s to employ the highest quality “specialists” they need to finance specific fellowships abroad – needs based – and trainees will travel knowing the type of job that they are coming home to.

6. Continued professional development needs to be encouraged, but not the current CME points accrual system. It astonishes me how few of our trainees are inquisitive – how little time is spent reading journals and researching dogma, how little time is spent in the library, how few “read” after passing their FCAI exam. Everything is easily obtained online now, everybody has smartphones and tablets – there is NO EXCUSE for anybody practicing anaesthesia not to be familiar with the contents of the current journals. On this site we share a twitter feed that points our visitors to worthwhile reading material. This is a strange phenomenon that appears specific to our specialty – can you imagine encountering an oncologist or a cardiologist that is unfamiliar with the latest literature in their field?

6. Continued professional development needs to be encouraged, but not the current CME points accrual system. It astonishes me how few of our trainees are inquisitive – how little time is spent reading journals and researching dogma, how little time is spent in the library, how few “read” after passing their FCAI exam. Everything is easily obtained online now, everybody has smartphones and tablets – there is NO EXCUSE for anybody practicing anaesthesia not to be familiar with the contents of the current journals. On this site we share a twitter feed that points our visitors to worthwhile reading material. This is a strange phenomenon that appears specific to our specialty – can you imagine encountering an oncologist or a cardiologist that is unfamiliar with the latest literature in their field?

Overall, congratulations to the College for a brave effort to brighten up the future of our specialty. We don’t know where it will lead, but with good husbandry, collegiality and engagement, we might have to “wear shades.”

* I see that the College has gotten so fed up with lack of trainee representation that they have created the Group of Anaesthetists in Training (to essentially replace the ATI), and are providing facilities, IT support and secretarial assistance. While this is wonderful, one has to wonder – why they had to do it?

Flotrac-Vigileo – useful tool or toy?

The Flotrac-Vigileo system appears to have become the first line haemodynamic monitor in Galway. How did this happen, and is it just a toy?

Over the past 2 decades there have been considerable advances in minimally invasive cardiovascular monitoring. This results from a greater acceptance of the flow-model approach to fluid resuscitation,1 a cultural shift away from pulmonary artery catheters (rightly or wrongly),2 and the now widespread acceptance that central venous pressure (CVP) does not predict fluid responsiveness.3 In essence, critical care practitioners now tend to combine data on arteriolar compliance (blood pressure), cardiac performance (stroke volume) and oxygen delivery-consumption (SvO2) when making decisions about fluids and vasopressors. The most popular non invasive devices to date are – oesophageal Doppler (useful, but huge user variability), PiCCO – which requires the placement of a femoral arterial line, and NiCCO – which uses the Fick principle to measure cardiac output from rebreathing CO2. None of these are simple to use, nor can they utilize monitors already in place. Hence, a device that measures stroke volume from a standard arterial line would appear to be a major step forward: assuming, of course, that it is accurate.

Over the past 2 decades there have been considerable advances in minimally invasive cardiovascular monitoring. This results from a greater acceptance of the flow-model approach to fluid resuscitation,1 a cultural shift away from pulmonary artery catheters (rightly or wrongly),2 and the now widespread acceptance that central venous pressure (CVP) does not predict fluid responsiveness.3 In essence, critical care practitioners now tend to combine data on arteriolar compliance (blood pressure), cardiac performance (stroke volume) and oxygen delivery-consumption (SvO2) when making decisions about fluids and vasopressors. The most popular non invasive devices to date are – oesophageal Doppler (useful, but huge user variability), PiCCO – which requires the placement of a femoral arterial line, and NiCCO – which uses the Fick principle to measure cardiac output from rebreathing CO2. None of these are simple to use, nor can they utilize monitors already in place. Hence, a device that measures stroke volume from a standard arterial line would appear to be a major step forward: assuming, of course, that it is accurate.

The Flotrac (sensor)-Vigileo monitor (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, Ca) calculates stroke volume and cardiac output from a single sensor attached to an arterial line at any site. Unlike PiCCO/PulseCO/LiDCO, it does not require external calibration, or the presence of a central line or specialized catheter. Since its introduction in 2006, the device has seen several software upgrades, with progressive improvement in accuracy: with time we can expect this device to improve further. We are now using the third generation of software,4 and this appears to be more accurate than previous versions.5

Flotrac-VIgileo combines rapid analysis in real time of the arterial pressure waveform with demographic data (such as gender, age, weight and height) applied to an evolving algorithm to calculate cardiac output. Arterial pulsatility is directly proportional to stroke volume. As changes in vascular tone and compliance occur dynamically, the device appears capable of correcting for this by analyzing skewness and kurtosis of the arterial waveform (more information here ). These correction variables are updated every 60 seconds and the arterial waveform is analyzed and averaged over 20 seconds, thus eliminating artifacts, jitter and premature contractions. Cardiac output is calculated utilizing the arterial waveform and the heart rate.

In addition to cardiac output, Flotrac-VIgileo (F/V) also calculates stroke volume variability, and hence fluid responsiveness.

An increasing number of studies have investigated this system. With each software update the device appears to be becoming more accurate. Mayer and colleagues6 meta-analysed studies to date. Earlier studies demonstrated poor correlation between F/V and thermodilution methods; with newer software the correlation has improved.7 It should be borne in mind, however, that thermodilution methods, although considered the gold standard, are not ideal devices to compare with F/V: measurement intervals and averaging times are substantially longer with all thermodilution methods. Hence it is possible that F/V is more sensitive to dynamic changes in cardiovascular activity. Conversely, it is likely the F/V is severely limited in patients with aortic valve disease (PMID: 21823375), those with intra-aortic balloon pumps in situ, those rewarming from induced hypothermia and patients with intra-cardiac shunts.

Recent studies have suggested that F/V is quite accurate at measuring changes in cardiac output associated with volume expansion (preload sensitivity)8 but not with changes associated the vasopressor use.9-11 In patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery, the F/V system was highly inaccurate during the critical phases of clamping/unclamping.12 It is likely that the accuracy also depends on the patient having a regular cardiac rhythm and minimal variability in tidal volume.13;14

So a mixed report on the Flotrac. Clearly, in terms of simplicity it is unbeatable: simplicity of placement, lack of observer error, continuity of data and the lack of need for secondary vascular access. In terms of accuracy– assuming that the patient is in a regular rhythm and has a reasonably stable respiratory pattern, it appears fairly reliable. I cannot see this being a device used intraoperatively, in the way the oesophageal Doppler has found its niche, due to significant inaccuracy in dynamic conditions. Nevertheless, in the ICU, in patients where haemodynamic monitoring may be beneficial – such as early sepsis, this is a useful tool. Is it better than a Swan? No, is anything? That will be topic of a future post.

References

1. Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 1368-77

2. Connors AF, Jr., Speroff T, Dawson NV, Thomas C, Harrell FE, Jr., Wagner D, Desbiens N, Goldman L, Wu AW, Califf RM, Fulkerson WJ, Jr., Vidaillet H, Broste S, Bellamy P, Lynn J, Knaus WA: The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 1996; 276: 889-97

3. Marik PE, Baram M, Vahid B: Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? A systematic review of the literature and the tale of seven mares. Chest 2008; 134: 172-8

4. Vasdev S, Chauhan S, Choudhury M, Hote M, Malik M, Kiran U: Arterial pressure waveform derived cardiac output FloTrac/Vigileo system (third generation software): comparison of two monitoring sites with the thermodilution cardiac output. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 1-6

5. De Backer D, Marx G, Tan A, Junker C, Van Nuffelen M, H++ter L, Ching W, Michard Fdr, Vincent JL: Arterial pressure-based cardiac output monitoring: a multicenter validation of the third-generation software in septic patients. Intensive Care Medicine 2011; 37: 233-40

6. Mayer J, Boldt J, Poland R, Peterson A, Manecke GR, Jr.: Continuous arterial pressure waveform-based cardiac output using the FloTrac/Vigileo: a review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009; 23: 401-6

7. Mayer J, Boldt J, Beschmann R, Stephan A, Suttner S: Uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis for less-invasive cardiac output determination in obese patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2009; 103: 185-90

8. Zhang Z, Lu B, Sheng X, Jin N: Accuracy of stroke volume variation in predicting fluid responsiveness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anesthesia 2011; 25: 904-16

9. Meng L, Phuong Tran N, Alexander BS, Laning K, Chen G, Kain ZN, Cannesson M: The Impact of Phenylephrine, Ephedrine, and Increased Preload on Third-Generation Vigileo-FloTrac and Esophageal Doppler Cardiac Output Measurements. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2011; 113: 751-7

10. Monnet X, Anguel N, Jozwiak M, Richard C, Teboul JL: Third-generation FloTrac/Vigileo does not reliably track changes in cardiac output induced by norepinephrine in critically ill patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2012;

11. Metzelder S, Coburn M, Fries M, Reinges M, Reich S, Rossaint R, Marx G, Rex S: Performance of cardiac output measurement derived from arterial pressure waveform analysis in patients requiring high-dose vasopressor therapy. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2011; 106: 776-84

12. Kusaka Y, Yoshitani K, Irie T, Inatomi Y, Shinzawa M, Ohnishi Y: Clinical Comparison of an Echocardiograph-Derived Versus Pulse CounterGÇôDerived Cardiac Output Measurement in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Surgery. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 2012; 26: 223-6

13. Khwannimit B, Bhurayanontachai R: Prediction of fluid responsiveness in septic shock patients: comparing stroke volume variation by FloTrac/Vigileo and automated pulse pressure variation. European Journal of Anaesthesiology (EJA) 2012; 29:

14. Saraceni E, Rossi S, Persona P, Dan M, Rizzi S, Meroni M, Ori C: Comparison of two methods for cardiac output measurement in critically ill patients. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2011; 106: 690-4

Hyperoxia and Surgical Site Infections: is oxygen beneficial?

Using high inspired concentrations of oxygen in the perioperative period may reduce the risk of surgical site infections for patients undergoing colo-rectal surgery. It does not appear to confer benefit for other patient groups.

We live side by side with an element that both feeds us and damages us simultaneously: oxygen. Reactive oxygen species cause lipid peroxidation of cell membranes and disrupt DNA. They interfere with gene expression and cause altered cell growth and necrosis. This happens all the time, and we have developed anti-oxidant scavenging systems for clearing up the debris. So oxygen is toxic. Conversely, oxygen kills bacteria – facilitating the activity of neutrophils, thus enhancing immune function, it is anti-inflammatory,1 it is a vasoconstrictor (may reverse vasoplegia) and it redistributes blood flow to the kidneys and splanchnic circulation.2-4 Oxygen is potentially therapeutic in sepsis.5

Surgical site infections (SSI) result in significant morbidity, delayed hospital discharge and increased healthcare costs. There is a known association between SSI and hypoperfusion, contaminated wounds, perioperative hyperglycaemia and hypothermia6 and obesity. It has long been proposed that the use of perioperative hyperoxia to high risk patients may result in a reduction in the risk of SSIs. The converse argument is that hyperoxia is toxic to the lungs7;8 and results in increased atelectasis and, potentially, an increase in postoperative pulmonary complications.9

The scientific rationale for preoperative hyperoxia is that oxidative killing by neutrophils, the primary defence against surgical pathogens, depends critically on tissue oxygenation.10 Hopf and colleagues11 performed a non interventional, prospective study of subcutaneous wound oxygen tension(PsqO2) and its relationship to the development of woundinfection in surgical patients. One hundred and thirty general surgical patients were enrolled and PsqO2 was measured perioperatively. There was an inverse relationship between wound oxygen tension and the risk of developing surgical site infections (SSI). They hypothesized that manipulating FiO2 may increase PsqO2 and reduce SSIs.

Grief et al12 randomly assigned 500 patients undergoing colorectal resection to receive 30 percent or 80 percent inspired oxygen during the operation and for two hours afterward. This was a very well constructed study. Anaesthetic treatment was standardized, and all patients received prophylactic antibiotic therapy, standardized fluid regimens and kept euthermic perioperatively. Wounds were evaluated daily until the patient was discharged and then at a clinic visit two weeks after surgery. The arterial and subcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen was significantly higher in the patients given 80 percent oxygen than in those given 30 percent oxygen. The duration of hospitalization was similar in the two groups. Among the 250 patients who received 80 percent oxygen, 13 (5.2 percent; 95 percent confidence interval, 2.4 to 8.0 percent) had surgical-wound infections, as compared with 28 of the 250 patients given 30 percent oxygen (11.2 percent; 95 percent confidence interval, 7.3 to 15.1 percent; P=0.01). The absolute difference between groups was 6.0 percent (95 percent confidence interval, 1.2 to 10.8 percent) NNT 15.

These data were confirmed by a smaller study from Spain. Belda et al13 undertook a double-blind, randomizedcontrolled trial of 300 patients aged 18 to 80 years who underwentelective colorectal surgery. Patients were randomly assigned to either30% or 80% fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2), intraoperatively,and for 6 hours after surgery. Anaesthetic treatment and antibioticadministration were standardized.A total of 143 patients received 30% perioperativeoxygen and 148 received 80% perioperative oxygen. Surgical siteinfection occurred in 35 patients (24.4%) administered 30% FIO2and in 22 patients (14.9%) administered 80% FIO2 (P=.04). Therisk of SSI was 39% lower in the 80% FIO2 group (relative risk[RR], 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.38-0.98) vs the30% FIO2 group. After adjustment for important covariates, theRR of infection in patients administered supplemental oxygenwas 0.46 (95% CI, 0.22-0.95; P = .04). Similar results were reported by Bickel and colleagues, in a 210 patients with acute appendicitis (5.6% versus 13.6%, p = 0.4, ARR 7 NNT – 13).14

Pryor et al claimed opposite results.15 This study included 165 patients that were undergoing general surgery, and were randomized to 30% or 80% oxygen. The overall incidence of SSI was18.1%. In an intention-to-treat analysis, the incidence of infectionwas significantly higher in the group receiving FIO2 of 0.80than in the group with FIO2 of 0.35 (25.0% vs 11.3%; P = .02).FIO2 remained a significant predictor of SSI (P = .03) in multivariateregression analysis. Patients who developed SSI had a significantlylonger length of hospitalization after surgery (mean [SD], 13.3[9.9] vs 6.0 [4.2] days; P<.001).

This study was criticized for a number of reasons. It is unclear whether or not the group assignment was truly blind. Tissue oxygenation was not blind. Wound infection was identified by retrospective chart review, a highly unreliable technique. There was no standardization of fluid therapy, temperature or antibiotic prophylaxis. Patients receiving80% oxygen were more likely to be obese, had longer operations,and lost more blood. All these factors may be associated withincreased risk of SSI. Significantly more patients in the high FiO2 group went back to the PACU intubated post op. Finally, the incidence of wound infections, at 25%, was high in the hyperoxic group compared with the study by Grief, 12 but similar to the control group in the study by Belda.13

Maragakis et al16 undertook a case-control retrospective review of SSIs in patients undergoing spinal surgery. Two hundred and eight charts were reviewed. The authors claimed that the use of an FiO2 of <50% significantly increased the risk of SSI (OR, 12; 94% CI, 4.5-33; P < 0.001). This study has the same flaws as that by Prior and colleagues,(50) albeit with opposite results.

Myles et al 17 enrolled a 2,050 patients into a study that randomized them to either FiO2 of 80% or 30%, plus 70% nitrous oxide. Patients that were given a high FiO2 had significantly lower rates of major complications (odds ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.56-0.89; P = 0.003) and severe nausea and vomiting (odds ratio, 0.40; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.51; P < 0.001). Among patients admitted to the intensive care unit postoperatively, those in the nitrous oxide-free group were more likely to be discharged from the unit on any given day than those in the nitrous oxide group (hazard ratio, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.73; P = 0.02). It is unclear whether these data represent a beneficial effect of oxygen or a detrimental effect of nitrous oxide.

The Proxi trial 18 included 685 patients in 14 Danish hospitals. Patients were randomized to 80% versus 30% oxygen. Temperature, fluid therapy and type of surgery were not controlled. Similar to the Pryor trial, the incidence of SSIs were in excess of 20% (20.1%) in the control group, not significantly different from the study group (19.1%). There was no difference in pulmonary complications between the groups. Clearly the extraordinarily high number of SSIs in both groups made a statistically significant difference in outcomes unlikely. A large number of patients had undergone emergency surgery and had contaminated wounds. Hence, a direct comparison with previous studies cannot be made.

However, comparisons have been made and here have been several meta-analyses (MA) of hyperoxia and surgical site infections. These differ in outcomes depending on whether or not one includes the Myles17 data. Where Myles’s study is included, the MA supports hyperoxia.19 Where it is excluded – MAs routinely exclude papers for reasons that are not always obvious – hyperoxia is shown not to be beneficial.20 My own conclusion is that there is tremendous heterogenicity between these studies: well controlled studies of colonic surgery where anaesthesia and perioperative care was standardised resulted in better outcomes. Poorly controlled studies (Pryor / Meyhoff), without standardisation resulted in very high levels of SSI in both groups. The excess adverse outcomes in the Pryor study suggests that there were substantial differences between the groups in terms of type and length of surgery, severity of illness etc. and that this study was fatally flawed.

My conclusion: if you are providing anaesthesia for bowel surgery, and will not be using nitrous oxide, 80% oxygen is unlikely to be harmful, and is potentially beneficial. Whether or not to extend this hyperoxia into the postoperative period is very controversial.

References

1. Nathan C: Oxygen and the inflammatory cell. Nature 2003; 17: 675-6

2. Bitterman H, Brod V, Weiss G, Kushnir D, Bitterman N: Effects of oxygen on regional hemodynamics in hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol 1996; 40: H203-H211

3. Cason BA, Wisneski J, Neese RA, Stanley WC, Hickey RF, Shnier CB, Gertz EW: Effects of high arterial oxygen tension on function, blood flow distribution, and metabolism in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 1992; 85: 828-38

4. Plewes JL, Farhi LE: Peripheral circulatory responses to acute hyperoxia. Undersea Biomed Res 1983; 10: 123-9

5. Bitterman H: Bench-to-bedside review: Oxygen as a drug. Critical Care 2009; 13: 205

6. Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R: Perioperative Normothermia to Reduce the Incidence of Surgical-Wound Infection and Shorten Hospitalization. New England Journal of Medicine 1996; 334: 1209-16

7. Fisher AB: Oxygen therapy, side effects and toxicity. Am Rev Respir Dis 1980; 122: 61-9

8. Bitterman N, Bitterman H: Oxygen toxicity. Handbook on Hyperbaric Medicine 2006; 731-66

9. Hedenstierna G, Edmark L, Aherdan KK: Time to reconsider the pre-oxygenation during induction of anaesthesia. Minerva Anestesiol. 2000; 66: 293-6

10. Overdyk FJ: Bridging the Gap to Reduce Surgical Site Infections. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2010; 111: 836-7

11. Hopf HW, Hunt TK, West JM, Blomquist P, Goodson WH, III, Jensen JA, Jonsson K, Paty PB, Rabkin JM, Upton RA, von Smitten K, Whitney JD: Wound Tissue Oxygen Tension Predicts the Risk of Wound Infection in Surgical Patients. Archives of Surgery 1997; 132: 997-1004

12. Greif R, Akca O, Horn EP, Kurz A, Sessler DI, The Outcomes Research Group: Supplemental Perioperative Oxygen to Reduce the Incidence of Surgical-Wound Infection. The New England Journal of Medicine 2000; 342: 161-7

13. Belda FJ, Aguilera L, Garcia de la Asuncion J, Alberti J, Vicente R, Ferrandiz L, Rodriguez R, Company R, Sessler DI, Aguilar G, Botello SG, Orti R, for the Spanish Reduccion de la Tasa de Infeccion Quirurgica Group: Supplemental Perioperative Oxygen and the Risk of Surgical Wound Infection: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 2005; 294: 2035-42

14. Bickel A, Gurevits M, Vamos R, Ivry S, Eitan A: Perioperative Hyperoxygenation and Wound Site Infection Following Surgery for Acute Appendicitis: A Randomized, Prospective, Controlled Trial. Archives of Surgery 2011; 146: 464-70

15. Pryor KO, Fahey TJ, III, Lien CA, Goldstein PA: Surgical Site Infection and the Routine Use of Perioperative Hyperoxia in a General Surgical Population: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 2004; 291: 79-87

16. Maragakis LL, Cosgrove SE, Martinez EA, Tucker MG, Cohen DB, Perl TM: Intraoperative Fraction of Inspired Oxygen Is a Modifiable Risk Factor for Surgical Site Infection after Spinal Surgery. Anesthesiology 2009; 110:

17. Myles PS, Leslie K, Chan MTV, Forbes A, Paech MJ, Peyton P, Silbert BS, Pascoe E, the ENIGMA Trial Group: Avoidance of Nitrous Oxide for Patients Undergoing Major Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2007; 107:

18. Meyhoff CS, Wetterslev J+, Jorgensen LN, Henneberg SW, H+©gdall C, Lundvall L, Svendsen PE, Mollerup H, Lunn TH, Simonsen I, Martinsen KR, Pulawska T, Bundgaard L, Bugge L, Hansen EG, Riber C, Gocht-Jensen P, Walker LR, Bendtsen A, Johansson G, Skovgaard N, Helt+© K, Poukinski A, Korshin A, Walli A, Bulut M, Carlsson PS, Rodt SA, Lundbech LB, Rask H, Buch N, Perdawid SK, Reza J, Jensen KV, Carlsen CG, Jensen FS, Rasmussen LS: Effect of High Perioperative Oxygen Fraction on Surgical Site Infection and Pulmonary Complications After Abdominal Surgery. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 2009; 302: 1543-50

19. Qadan M, Akca O, Mahid SS, Hornung CA, Polk HC, Jr.: Perioperative Supplemental Oxygen Therapy and Surgical Site Infection: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Archives of Surgery 2009; 144: 359-66

20. Al-Niaimi A, Safdar N: Supplemental perioperative oxygen for reducing surgical site infection: a meta-analysis. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2009; 15: 360-5

This review copyright Patrick Neligan 2012. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

Acute Respiratory Distress in the Recovery Room (tutorial)

Clinical Scenario: A 57 year old male undergoes upper abdominal surgery. He refused an epidural. The intraoperative course was uneventful. He was given 2mg hydromorphone in the OR. He was extubated, breathing 360 ml tidal volumes; arousable. Shortly after arrival to the recovery room, the patient develops acute respiratory distress. His respiratory rate increases to 33 breaths per minute, SpO2 is 92%, heart rate increases to 110 beat/min, blood pressure 98/50 mmHg. On examination, his pupils are pinpoint but reacting, he is moving air into both of his lungs but there is little air entry into his lung bases.

A non-rebreather facemask is placed: his SpO2 remains 92%.

1. Identify the problem

What is the principle diagnosis?

The patient is clearly in acute respiratory distress; however the cause and reversibility of the problem are unclear. It is imperative that the bedside clinician have a systematic approach to diagnosis and management. The cause of the problem may lie at any stage in the process of initiating a breath to exchanging gas. This tutorial focuses on the diagnosis.

Patients in recovery room with acute respiratory distress have one or more of the following three problems: failure to ventilate, as characterized by a high PaCO2, failure to oxygenate, as characterized by low PaO2, or failure to maintain their airway (figure 1). All three may co-exist: for example, a patient that receives excess opioids my hypoventilate, obstruct their airway due to opioids and carbon dioxide narcosis, and become hypoxic due to absorption atelectasis, failure to replenish alveolar oxygen and alveolar CO2 buildup. Nevertheless, the primary problem is failure to ventilate, due to central loss of respiratory drive. Hence, to make a diagnosis, one needs to identify the primary problem.

Figure 1: Mechanisms of Acute Respiratory Distress in recovery room

Figure 1: Mechanisms of Acute Respiratory Distress in recovery room

There are three major components to the respiratory apparatus:

- Central chemoreceptors: in the brainstem that detect carbon dioxide and initiate the respiratory pump. This requires an intact brainstem and cervical nerve roots.

- The respiratory pump: the phrenic nerves (and on occasion the intercostals nerves) initiate diaphragmatic contraction. This requires and intact neuromuscular junction and sufficient diaphragmatic muscular tissue to increase the volume of the thoracic cavity. This leads to increased negative pressure within the pleura, stretching the alveoli. Flow of gas into the alveoli is known as ventilation.

- Alveolar-capillary interface: gas must flow across the alveolar capillary interface to enter and leave the blood. This is known as ventilation perfusion matching and is reliant on alveolar gas volume (particularly in end expiration – the functional residual capacity) and pulmonary blood flow.

The problem is either central – a problem of respiratory drive, peripheral – a problem of the respiratory pump, large airway – a problem of gas transfer, or alveolar – a problem of gas exchange (figure 2).

- Central Ventilation: the neurologic system is not activating respiration in response to an increase in arterial CO2 tension

- Peripheral Ventilation: the thoracic pump (chest and diaphragm) is not effective in guaranteeing adequate minute ventilation.

- Gas Transfer: air does not pass effectively from the upper to the lower airway due for example to increased airway resistance.

- Gas Exchange:

- Gas does not to pass effectively from alveoli to capillaries due to a pathologic process in the interstitial space (diffusion defect).

- Ventilation is being wasted – alveoli are being ventilated but not perfused: dead space ventilation or more air than the blood can utilize (high ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) ratio the extreme version being dead space ventilation).

- Blood flow is inadequately utilized and blood is passing through the lungs without coming into contact with aerated alveoli: perfused but not ventilated – shunt or ventilation falls behind blood flow (low V/Q ratio the extreme version being right to left shunt).

2. Understand the problem

What is the mechanism of injury?

Ventilation Failure

Failure to ventilate is the most common cause of acute respiratory distress in the recovery room. It is characterized by reduced alveolar ventilation which manifests as an increase in the PaCO2 > 50 mmHg (6.5kPa). The best method of classifying this is to follow the respiratory pathways from the brainstem to the alveoli, and then ask whether a pathology exists at each particular site. Often patients have multiple problems: e.g. narcosis, pulmonary edema, pleural effusion, obesity

Neurological

Central: loss of ventilatory drive due to general anesthetic agents (propofol principally), benzodiazepines, narcosis, stroke or brain injury

Spinal: spinal or epidural anesthesia; spinal cord injury, cervical – loss of diaphragmatic function, thoracic – loss of intercostals.

Peripheral: phrenic nerve injury in neck or thoracic surgery

Muscular

Persistent neuromuscular blockade; diaphragmatic trauma; myopathic disorders – myasthenia gravis (patient post op thymectomy).

Anatomical Problems

Chest Wall – flail chest; intra-abdominal hypertension (abdominal packs placed).

Pleura – pleural effusions, pneumothorax (patient post op thoracic or retroperitoneal surgery: nephrectomy, abdominal aortic aneurysm, esophagectomy).

Airways – airway obstruction: laryngeal edema, inhalation of a foreign object (tooth or throat pack), bronchospasm.

Oxygenation Failure

Oxygenation failure occurs at a microscopic level at pulmonary capillary-alveolar interface. Two different injuries can occur at this level, either individually or in combination:

Diffusion abnormality – thickening of the alveoli (pulmonary fibrosis). There is an obstruction to effective gas exchange due to material in the interstitial space. The patient will have an antecedent history of hypoxemia.

Ventilation/Perfusion Mismatch: Dead Space Ventilation (or high V/Q): alveoli are ventilated but not perfused. This is unusual in the extubated patient, an usually results from significant hypovolemia

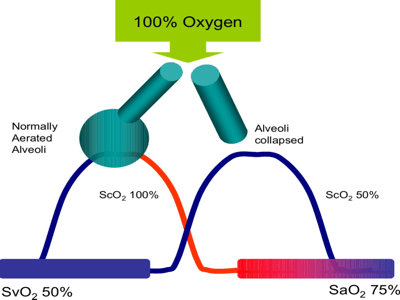

Figure 2 Causes of Respiratory Failure

Ventilation Perfusion Mismatch (figure 3): this occurs when lung units well perfused but poorly ventilated. The extreme version is right (as in right side of the heart) to left shunt (blood flows through the lungs without coming into contact with aerated lung tissue. This lung injury is resistant to oxygen therapy. This frequently occurs in patients that have upper abdominal or chest surgery secondary to segmental lung collapse – atelectasis. Atelectasis may actually be worsened by oxygen therapy, due to rapid reabsorption.

Less severe, and usually oxygen sensitive, ventilation-perfusion mismatch is the inevitable consequence of major surgery. The time constants in many lung units are altered due to edema in the lung tissue and secretions in the major and minor airways. This results in an alteration of the dynamics of gas transport: alveolar oxygen tension is slower to be replenished, carbon dioxide is more slowly removed.

Figure 3: Ventilation-Perfusion Mismatch. Alveolar unit A has normal ventilation and perfusion, hence the pulmonary capillary (arterial side) oxygen tension (PcO2) is 100mmHg (13kPa). Unit C is ventilated but not perfused. It does not contribute to gas exchange. Unit B is partially ventilated, but due to it’s long time constant (due to secretions), the alveolar oxygen tension is below normal, and the PcO2 is reduced to 70mmHg (9kPa). When all lung units are accounted for, the result is hypoxemia (PaO2 70mmHg/9kPa)

Figure 4: Oxygen therapy effectively treats ventilation perfusion mismatch by increasing the fraction of gas in the alveolus that is oxygen, thus increasing the PAO2 (alveolar O2). It also reverses pulmonary vasoconstriction and reduces dead space.

Figure 5: Right to left intrapulmonary shunt: in this example, 50% of the pulmonary circulation is flowing thru collapsed lung tissue. Because hemoglobin can only be saturated to 100%, regardless of the quantity of oxygen that is delivered to normal lung tissue, it is not possible to compensate for the intra-pulmonary shunt.

3. Differential diagnosis / Work the problem

How do you make the diagnosis?

Acute respiratory failure is usually a problem of either failure to oxygenate, as characterized by a low PaO2, or failure to ventilate, as characterized by a high PaCO2. Where hypoxemia and hypercarbia co-exist, oxygenation should be considered the primary problem.

Figure 6: Assessing the Patient with Acute Respiratory Failure

The key to making the diagnosis is to look at the patient’s breathing pattern. If the patient is taking slow shallow breaths, with normal synchrony between opening of the mouth to inhale and movement of the chest outwards and downwards, then the problem is most likely ventilatory failure secondary to central respiratory depression. This most commonly results from opioid administration, but may also follow the administration of midazolam/lorazepam or discontinuation of a propofol infusion.

If the patient is taking rapid shallow breaths, the problem is either ventilatory failure secondary to a peripheral problem or oxygenation failure secondary to ventilation-perfusion mismatch. The key to separating the two is the clinical circumstance and the presence or absence of hypoxemia (low SpO2 or requirement for high FiO2). In the absence of hypoxemia, a neuromuscular problem should be considered – such as residual neuromuscular blockade or a dense epidural block that paralyses the intercostal muscles. One also sees this pattern in patients with low physiologic reserve, the malnourished and the critically ill. In patients that have undergone thoracic surgery or retroperitoneal surgery, a high clinical suspicion for pneumothorax should be considered. This is characterized by hypoxemia, unilateral breaths sounds, and, in severe cases, hypotension.

Rapid shallow breathing with hypoxemia is caused by ventilation perfusion mismatch. This is usually caused by retained secretions and/or atelectasis. This most commonly occurs in patients that have undergone abdominal surgery, are morbidly obese or have been positioned intraoperatively in the Trendelenberg position.

Pulmonary embolism should be suspected in patients that have undergone pelvic or hip surgery with rapid shallow breathing and hypoxemia, associated with tachycardia and hypotension.

An obstructed breathing pattern is suggestive of upper or middle airway pathology. The problem is caused by central loss of pharyngeal tone, and soft tissue obstruction (associated with depressed level of consciousness and anesthesia) or mechanical obstruction to the airway, above, at the level of or below the glottis. Classically the patient has nasal flaring, supraclavicular or intercostal retraction, and a see-saw chest movement: the chest moves inwards as the diaphragm descends. The patient may have inspiratory stridor (supraglottic obstruction), expiratory stridor (glottic or subglottic obstruction) or expiratory wheeze (bronchospasm). Typically hypoxemia is a late complication of airway obstruction. This is important as hypoxia may be rapidly followed by bradycardia and asystole.

4. Solve or resolve the problem

This patient has many risk factors for acute respiratory distress. Does he have ventilatory failure? Quite possibly – he may be narcosed from excessive interoperative opioids. He may be hypoventilating due to splinting (upper abdominal pain due to surgical incision) or persistent partial neuromuscular blockade. He may have upper airway obstruction, due to loss of pharyngeal tone, obstruction with a bite block, laryngeal edema or laryngospasm. He may have severe bronchospasm, and inhaled foreign object (such as a tooth) obstructing a major bronchus, or the presence of blood or gastric contents aspirated from the upper airway. He may have lower airway collapse due to hypoventilation and or absorption atelectasis, diffusion hypoxia (due to oxygen being displaced by nitrous oxide in the alveoli) or alveolar fluid, due to excessive intravenous administration.

Working the problem:

Step 1: Is this failure to oxygenate or failure to ventilate?

The patient has rapid shallow breathing with hypoxemia – this is failure to oxygenate, it may be secondary to peripheral ventilatory failure, or primary to V/Q mismatch.

Step 2: Is this peripheral ventilatory failure or primary V/Q mismatch?

The patient has bilateral air entry into the upper segments of the lungs, with little air entry into the bases. This is primary V/Q mismatch secondary to atelectasis. The patient has an intra-pulmonary shunt, evidenced by the lack of responsiveness to oxygen therapy.

Step 3: How is the diagnosis confirmed?

The diagnosis may be accepted, clinically (there is sufficient clinical suspicion in this case) or confirmed by chest x-ray and arterial blood gas sampling.

Step 4: What is the initial management of this patient?

The patient should nursed in the upright or seated position – the effect of gravity is to recruit lung tissue and increase functional residual capacity. The patient should be encouraged to cough, to mobilize secretions. Consideration should be given to devices that assist in lung recruitment such as incentive spirometry or the use of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. If the problem worsens or fails to resolve, the patient should be re-intubated and lung recruitment achieved using an ICU grade mechanical ventilator.

5. Conclusions

- The assessment of the patient with acute respiratory distress involves taking a history, examining the patient and quantifying the degree of respiratory injury.

- This involves determining whether the problem is failure to ventilate, failure to oxygenate or failure to maintain the airway.

- Failure to maintain the airway leads to failure of gas flow and ultimately hypoxemia and hypercarbia. The problem is either central loss of airway patency or mechanical airway obstruction.

- Failure to oxygenate is caused by ventilation perfusion mismatch: the patient typically has a rapid shallow breathing pattern.

- Failure to ventilate is caused by a problem in the central nervous system or a problem with the thoracic pump: the patient typically has a slow shallow breathing pattern.

- Failure to ventilate is an ominous sign.

- Look for an immediately reversible cause of failure to ventilate – such as narcosis, deep sedation or persistent neuromuscular blockade.

- In the absence of a reversible cause, positive pressure ventilation is required.

Figure 7: Failure to Oxygenate vs Failure to Ventilate

This article is entirely the work of Patrick J Neligan MA MB FCAI FJFICM. No part of this article or its illustrations may be reproduced without the author’s permission. Select illustrations were developed in conjunction with Maurizio Cereda MD. © PJN 2012

Agitation and Pain in the Recovery Room (tutorial)

Problem:

A 43 year old male returns from the operating room following cholecystectomy. The operation had been originally planned using the laparoscopic approach. However it became necessary to convert to an open procedure. Intraoperatively the patient received fentanyl 300mic/g, propofol, vecuronium, oxygen and desflurane and cefazolin. At the end of surgery, neuromuscular blockade (sustained tetanus was demonstrated) was reversed, the patient opened his eyes and was extubated.

On arrival to the recovery room the patient is combative, thrashing around, incoherent, not obeying commands, attempting to remove has urinary catheter. His pulse rate is 120 beats per minute, blood pressure 170/100, temperature 37.0 degrees Celcius and his pulse oximeter is reading an SpO2 of 99%.

1. Identify the problem

What is the mechanism of injury and what are the treatment options?

This patient is agitated: the most common cause of postoperative agitation is pain. Pain is a neurohormonal and emotional response to a noxious stimulus, in this case surgical injury. Pain is the “fifth vital sign.”

Pain is known to worsen perioperative outcomes: it results in – increased protein catabolism – thereby reducing physiologic reserve, retention of salt and water, impaired wound healing, prolonged recumbent times (resulting in increased risk of deep venous thrombosis), and significant suffering and dissatisfaction on the part of the patient. Elevated adrenergic activity results in increased oxygen demand and may precipitate myocardial ischemia. In patients, such as in this case, that undergo upper abdominal surgery, the splinting effect of pain results in impaired coughing and lung derecruitment and increased risk of pulmonary complications including nosocomial pneumonia.

One of the major roles of perioperative clinicians is to minimize patient suffering. Patients universally report dissatisfaction with perioperative pain management.1 Modern approaches to preventing suffering in perioperative patients include a multimodal approach to pain, postoperative nausea and vomiting, anxiety, agitation and delirium.2-5

2. Understand the problem

What is pain (understanding the mechanisms)?

Table 1. Inflammatory Mediators that amplify the pain response |

|

Substance |

Source |

| Norepinephrine | Nerve endings & circulating |

| Epinephrine | Circulating |

| Substance P | Nerve endings |

| Glutamate | Nerve endings |

| Bradykinin | Plasma kininogen |

| Histamine | Platelets, mast cells |

| Hydrogen Ions (acidity) | Ischemia / Cell Damage |

| Protaglandins | Arachidonic acid / damaged cells |

| Interleukins | Mast Cells |

| Tumor necrosis factor alpha | Mast Cells |

Surgical incision is associated with tissue injury and release of inflammatory mediators, development of local edema and activation of nocioceptors. These are nerve endings of myelinated (A-delta) and unmyelinated (C) afferent nerve fibres that respond to noxious thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimulation. A-delta fibres are mechanothermal while the C fibres are polymodal.

When nociceptors are activated, a series of neurohormonal reflexes are activated, and a painful sensation is elicited.6 In the awake patient, this is apparent by an adverse emotional response, a sensation of “unpleasantness”. In a sedated patient this may result in hyperadrenergic activity, agitation or aggressiveness.

Figure 1: Pain Pathways

1. The nocioceptive response is activated at the level of the surgical incision; 2. release of inflammatory cytokines and vasodilator metabolites; 3 transmission of nocioceptor impulses along afferent A-delta and C fibers; 4. integration and amplification in the spinal cord – c”windup”; 5 transfer of impulses from doral horns to thalamus and post-central gyrus; 6. activation of hypothalmo-pituitary adrenal axis; 7 release of cortisol, epinephrine and norepinephrine; 8 central and peripheral sensitization .